Does Moat Investing Work?

Why competitive advantages alone don't guarantee investment success

This summer, I spoke at CFA Society Rochester's monthly luncheon on the topic of management and moats. You can view the full presentation here.

During the Q&A session, one question cut straight to the chase: “Does moat investing work?”

I’d just spent 45 minutes talking about the benefits of economic moats, but I realized I hadn’t addressed the one question most likely on everyone’s mind.

So…does it work?

From a business standpoint, the benefits of moats are obvious.

From an investing standpoint, however, you want to know if companies with economic moats can generate strong returns that beat the market over the long term.

It’s a fair question - and one that I wish I’d addressed more thoroughly, which is why I’m writing this post. But the more I’ve thought about it, the question “Does moat investing work?” is much like asking, “Do eggs make a good cake?”

Eggs are a key ingredient for making a good cake. Eggs are usually included in good cakes; however, they’re not necessary for making a good cake. Importantly, a cake that uses eggs can be ruined if the other ingredients are rotten.

Similarly, moats are often an attribute of successful long-term investments, but they aren’t necessary for strong returns and moats may not produce strong returns if the other key ingredients (i.e. management, price) aren’t present.

As I discussed in my series on economic moats, the value of a moat is that it gives management time to make decisions. The moat itself is not the economic engine - its job is to protect the castle. Management’s goal should be to use the moat and the time it affords to build a bigger castle and ideally further widen the moat.

Consequently, you should seek companies with moats that are also run by excellent management teams who are best suited to that task.

My presentation discussed why it’s preferable to own companies led by stewards of capital rather than professional managers. I outlined some of the stewardship traits I look for, such as intrinsic motivation, thoughtful capital allocation, and setting the cultural tone of the business.

Even with a moat in place, management can use the time unwisely and make bad decisions that erode the castle it’s meant to defend. Indeed, one downside of moats is that they can breed complacency, especially in low growth industries. We’re seeing this at work today in the consumer staples sector.

For decades, companies like Procter & Gamble, Unilever, and Kraft Heinz leveraged their well-known brands, scale, and distribution advantages to charge premium prices. When a blueprint for success has worked for a long time, employees and management aren’t incentivized to challenge the status quo and disrupt itself before someone else does. Further, their generous dividend commitments limited their financial flexibility to adequately respond to upstart challengers and private label growth.

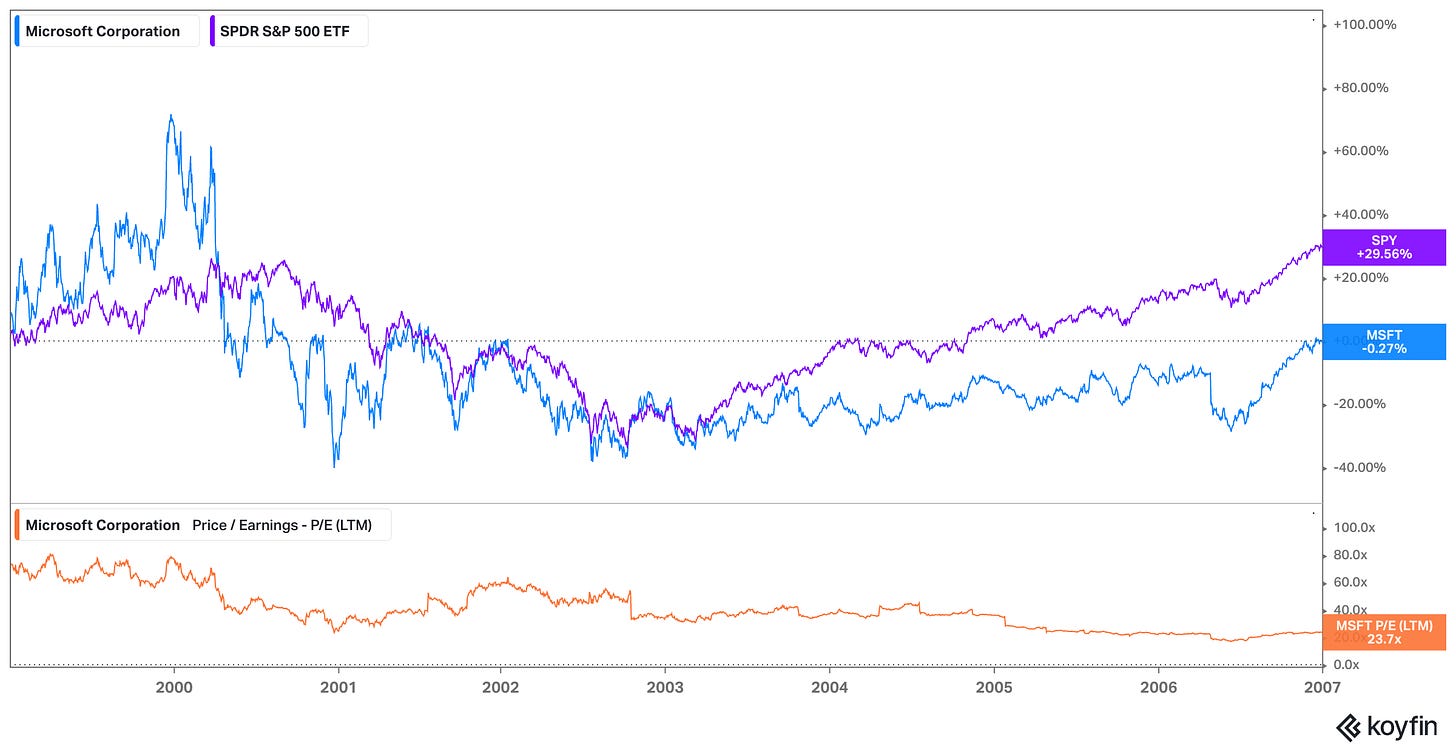

You can also overpay for a business with an economic moat, which can lead to poor investment returns. For example, if you bought Microsoft shares in January 1999 and held patiently for eight years, you watched Microsoft the business more than double its revenue and increase earnings per share by over 80% during the subsequent eight years, but Microsoft the investment was flat on a total return basis and underperformed the market over the same period. Despite good fundamental performance, Microsoft failed to meet the lofty expectations baked into its starting P/E ratio of 70x and by 2007 its P/E stood at 24x. (Eventually Microsoft went on to do just fine, of course, but eight years is a considerable stretch.)

It’s true that great businesses that stay great can justify their premium multiples (up to a point) and sustain high ROIC for longer than would be anticipated. As Buffett reminds us, “time is the friend of the wonderful company, and the enemy of the mediocre one.”

But as Michael Mauboussin and Alfred Rappaport write in their book Expectations Investing:

“The key to successful investing is to estimate the level of expected performance embedded in the current stock price and then assess the likelihood of a revision in expectations.”

The higher the current expectations, the less the opportunity for outperformance. Great companies with moats tend to have high expectations, so it’s important to understand how your view of a company with an economic moat differs from the market’s implied expectations.

Ok, but what about backtesting?

Moats are a qualitative judgement - e.g. wide vs. narrow width, positive vs. negative trend, deep vs. shallow depth - and therefore difficult to backtest the way you might examine “value” or “momentum” factor performance.

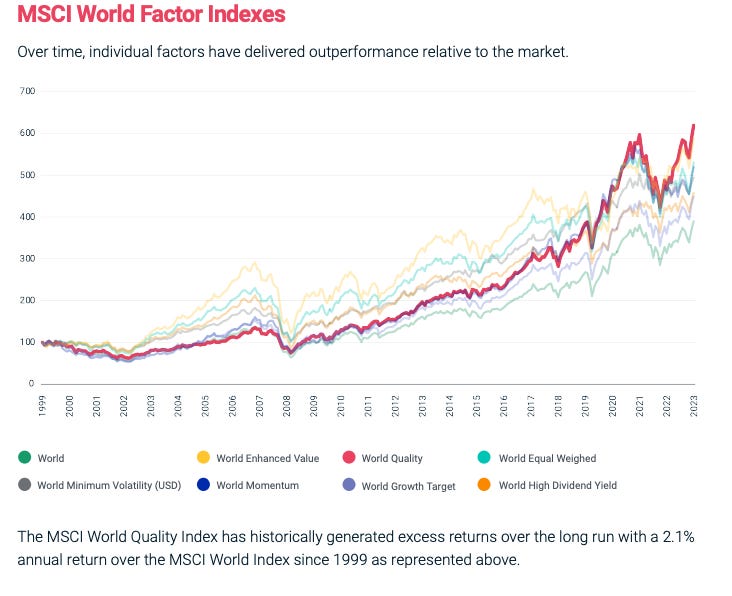

The closest proxy might be the “quality” factor, which generally looks for high return on equity, low debt/equity, and low earnings variability. These are common outputs for moat-worthy companies, though observe that this formula includes management capital structure decisions and isn’t solely focused on operational performance.

That aside, the quality factor’s strong historical performance in various studies is encouraging, as shown below.

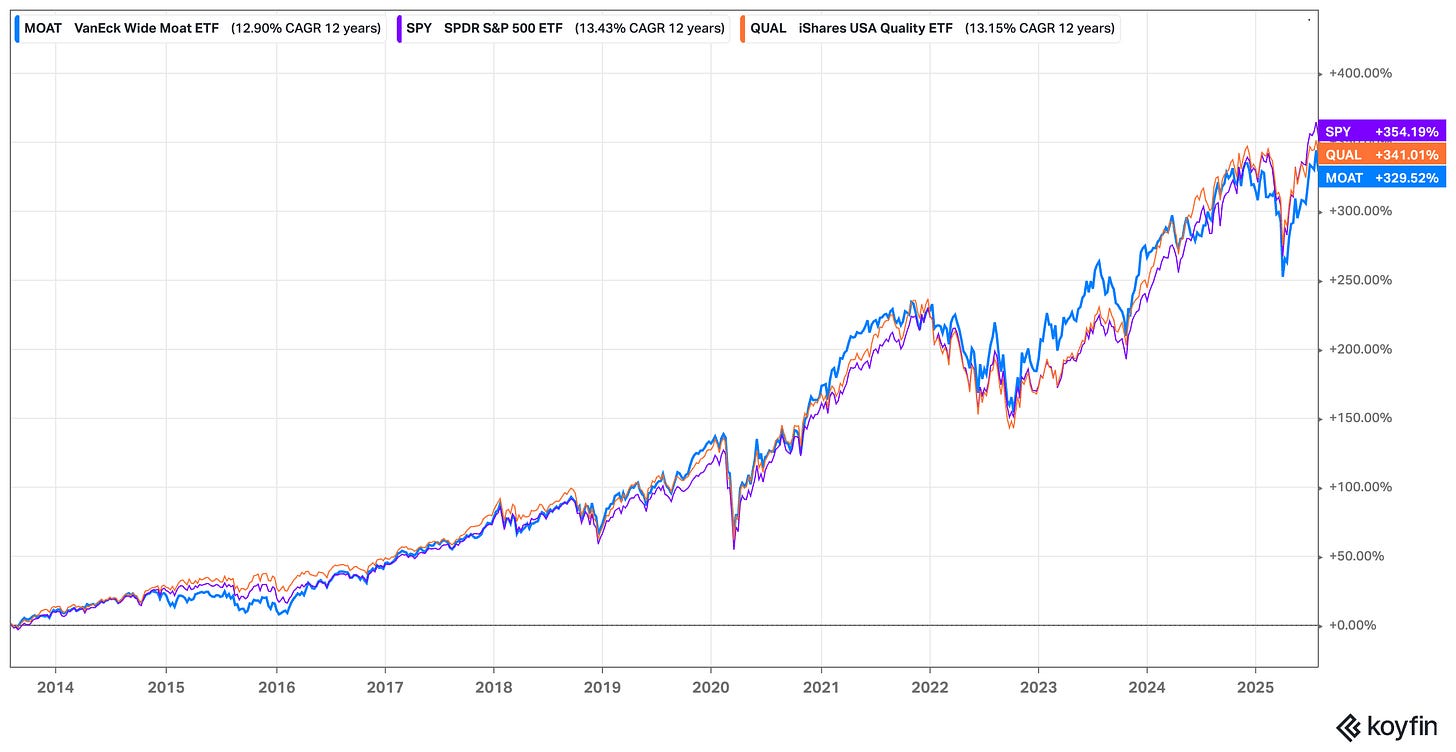

Morningstar’s Wide Moat Index is the longest-running “moat” focused, broad-based instrument I know of that uses analyst-driven moat ratings and also takes valuation into consideration for determining portfolio inclusion and weighting. As the below chart shows, it’s had periods of over- and under-performance versus the SPY and QUAL (iShares MSCI USA Quality Factor) ETFs, but its performance has been broadly in-line since August 2013 (when QUAL was launched).

In all, there’s intuitive, anecdotal, and statistical support for economic moats contributing to good investment results, but, ultimately, while economic moats are desirable in an investment, they are not sufficient on their own. Just as a good cake requires more than just eggs, durable competitive advantages must be paired with exceptional management and an attractive price to bear fruit. It is the combination of moat, management, and valuation that truly builds the foundation for long-term investment success.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

Todd Wenning is the founder of KNA Capital Management, LLC, an Ohio-registered investment advisor that manages a concentrated equity strategy and provides other investment-related services.

At the time of publication, Todd, his immediate family, and/or KNA Capital Management, LLC or its clients do not own shares of any company mentioned.

Please see important disclaimers.

Great analogy with the cake example. Totally agree that moats matter, but without disciplined management and a reasonable entry price, they can still disappoint. That Microsoft example really drives it home.

Your content is gold, keep it coming!

Outstanding post; good reminders of what to think about when assessing a company. Makes one wonder whether FICO today is MSFT during early 2000s-