Howdens Joinery: Additional Thoughts

Responding to reader questions and my takeaways from the founder's new book

My recent post on Howdens Joinery brought in a lot of questions and comments from readers on both sides of the pond, so I wanted to address some of those topics in a separate post.

Before I get to those, I recently read Howdens Joinery founder Matthew Ingle’s book called Kitchens, or Sink (2022). While Ingle is no longer actively involved in Howdens, the book provided insight into Howdens’ DNA and operations and is thus a worthwhile read for anyone interested in the business.

Here are a few key takeaways for investors.

Company DNA

One of the patterns I’ve picked up on over time is that companies that came through traumatic experiences have often learned critical lessons that lead to positive long-term strategies.

In 1992, U.S homebuilder NVR, for example, went bankrupt partly due to failed speculative land development ventures. When it emerged a year later, it swore off land development altogether and would control all its land through options rather than outright purchase. Today, legacy and upstart homebuilding competitors regularly imitate NVR’s capital-light strategy, but rarely duplicate it.

Similarly, it’s clear from reading Ingle’s book that his experiences at British retailers Magnet and MFI defined his approach at Howdens.

The short version of Howdens’ and Ingle’s history – they’re intertwined – is that Ingle’s great-grandfather founded Magnet, a kitchen and joinery retailer. After moving up the company ranks at Magnet, Ingle found himself in a tough spot as the retailer ran into tough times in the late 1980s and early 1990s. As a result, his family members were ousted from the business. In 1994, Ingle was fired after Magnet was acquired.

Ingle soon joined MFI, a furniture and kitchen retailer. It was inside MFI that Ingle came up with the idea for Howdens, which would focus on selling only kitchen and joinery products to trade customers through small depots. Under MFI, Howdens grew nicely, but the rest of MFI struggled. Ingle would eventually become CEO in 2005 amid a reorganization.

Ultimately, only Howdens remained, but the company took on all the pension liabilities and financial debt of the legacy MFI operations.

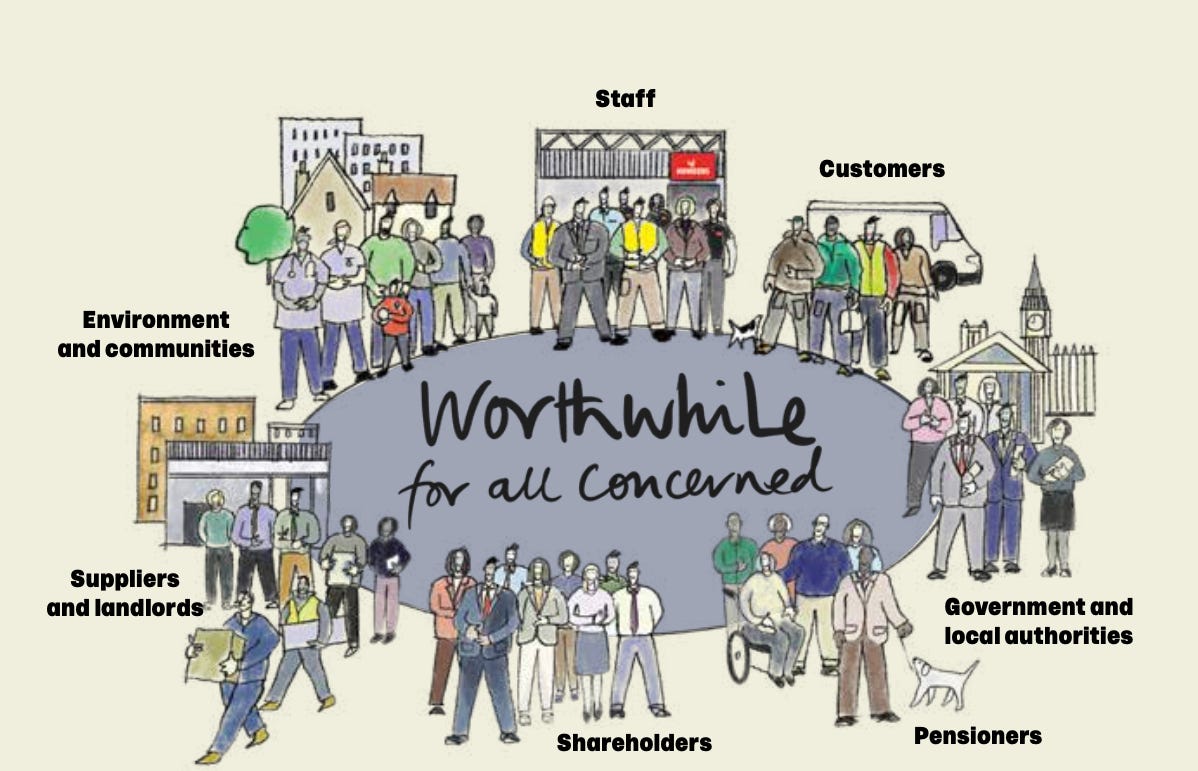

As an investor in Howdens, it’s important to understand this history. First, it helps explain the company’s financial conservatism. Second, it also helps explain why the company aims to be “worthwhile for all concerned” – i.e., stakeholders – because Ingle had firsthand seen the impact of financial and operational mismanagement on communities, employees, suppliers, and shareholders.

New management

Founder transitions can be messy. Founders often struggle to separate themselves from the business, or the new CEO tries too hard to distance themselves from the founder.

This is not the case at Howdens. As early as 2014, Ingle contemplated his departure from the company and, a year later, told the chairman it was time to start a CEO search. In July 2017, they announced that Andrew Livingston would become CEO in 2018.

Ingle notes in the book that while it took them a long time to find his replacement, the vital thing to him was to get it done right, no matter how long it took.

He speaks highly of Livingston, noting:

“Andrew was at Screwfix and at B&Q before coming to Howdens. It may have taken us some time to find him, but it was worth it. You need exactly the right person; someone who is capable; someone who has a proven track record; and someone who really wants to do the job. Like me all those years ago, I believe Andrew is the right man in the right place at the right time.”

Importantly, Ingle didn't want to lurk in the shadows of the C-suite and made a clean departure from the firm's operations.

To both Ingle’s and Livingston’s credit, the business has performed well since Ingle’s departure, and the stock price is up about 65% since the transition.

Depot bonus scheme

Ingle spells out the bonus scheme for depot managers and staff in the book.

“So we developed a Lapeyre-style (a French retailer) bonus model in which the manager would receive 5 per cent of the local profit margin, minus any stock loss, and their staff would receive another 5 per cent of the local gross margin, divided by the number of staff. A completely simple system in which everyone is motivated, and everyone is rewarded. Our staff are responsible for the business – and they’re rewarded for being responsible for the business.”

He illustrates the potential earnings with the following example:

“But as the Howdens business has developed there are of course many instances where there are depots selling as much as, say £3 million a year, on a gross margin of 60 per cent, which is £1.8 million, minus costs, which might mean you’re making a profit in excess of a million pounds a year, which at 5 per cent amounts to £50,000 for the depot manager, plus another £50,000 to staff.”

In the above example, the profit pool implies a depot-level margin of 33%, but Ingle says it could be more. Assuming 33% across Howdens’ depot locations, here’s what the average depot manager (and staff) bonus looked like over the past eight years.

As you can see, the bonus has been consistent, with a clear bump in the past two years due to solid kitchen remodel demand.

This incentive structure supports Howdens’ moat. Because Howdens’ prices are determined at the depot level and aren’t published, depot managers take ownership of pricing and costs. As such, they are financially incentivized to grow but only at appropriate margins. Put differently, they need to grow only when it creates value for the depot. Hiring an additional person at the depot, for example, dilutes the staff bonus pool unless that new person creates enough value to offset their cost.

If each Howdens depot is managed correctly, it will be challenging to compete with at the local level; if that's the case across most of its 880+ depots, then the company at large will have an economic moat.

Indeed, one of the core messages of Bruce Greenwald’s book, Competition Demystified, is that moats are intrinsically local and then aggregate into a broader moat. He writes:

“The best course is to establish dominance in a local market, and then expand outward from it…Economies of scale, especially in local markets, are the key to creating sustainable competitive advantages…An attractive niche must be characterized by customer captivity, small size relative to the level of fixed costs, and the absence of vigilant, dominant competitors…The key is to ‘think local.’”

Greenwald shows in his book this is how Wal-Mart began its ascendance - by winning at the local level. Howdens plays a different game from Wal-Mart, of course, but the key is that the incentives foster actions at the depot level that make it difficult to compete against.

Worth a read?

Beyond my interest in Howdens, Ingle’s book was well worth a read. It’s a quick read with short chapters (always appreciated!) and similar sketch illustrations as what you find in Howdens top-notch annual reports.

You'll get something out of it if you're an entrepreneur, manager, or in the C-suite. I particularly liked his "Skipton Market Rules" which he picked up observing vendor stands at a local market.

Make money: Ensure you have more money at the end of the day than you started with.

Be the best: Always turn up, sell good produce, be answerable to your every decision.

Remember, it’s your stall: Do you own thing, specialize.

Your reputation: We’ve got all the time in the world to build a reputation…so no time to lose.

He adds: “Do something that you’re good at, that makes money, that gives the customer what they want, when they want it, and at the right price, and for goodness’ sake DO NOTHING ELSE. That’s Skipton Market Rules.” (his emphasis)

Thoughts on international expansion

After publishing my piece on Howdens, I received several questions about the company's expansion in France and Belgium. In 2021, Howdens closed five French depots, and, as the chart below shows, revenue per depot lagged the performance of the U.K. business.

This begs the question, is the venture worth it?

While Howdens has been in France since 2005, depot growth in the region only accelerated in recent years. Naturally, newer depots will have lower sales than more mature locations do.

As the slide below describes, Howdens’ strategy is to create dense depot networks around urban areas, with Paris being the focus of the growth. In the 2021 annual report, management noted that the reason the five locations were closed was because they did not support its “city-based” expansion strategy, which was established in 2019.

One of the challenges with the French market relative to the U.K. market is that France has nearly four times the square mileage as Great Britain (88,000 versus 213,000) and about half the population density. This adds some cost to the system (e.g., supply chain, marketing, etc.), and, as such, it will take some time for Howdens to build sufficient scale in the region. From an outsider's perspective, focusing first on Northern France and Belgium and working south may have been a better strategy.

On the bright side, France has similar homeownership rates (about 60%) and GDP per capita as the U.K. In all, it is a worthy market for investment, but investors should monitor progress closely. If revenue per depot doesn't improve as newer locations mature, that could be a sign that the city-based strategy isn’t working.

Others had feedback on my comment that there's an opportunity for Howdens to push into the U.S. market - particularly the Washington, DC metro area, which features high population density, a robust housing market, and the potential for vertical integration being so close to the Southeastern wood basket.

As I noted in the original post, that's wild speculation on my part, and it may indeed be true that Howdens is managed too conservatively for a U.S. venture. And yes, U.K. and U.S. retailers have struggled to expand in each other's markets successfully. I made that mistake investing in Tesco years ago, so I understand that risk well.

All that may be true, but if there is indeed an opportunity for Howdens to use its unique business model and create shareholder value in the U.S., management should seriously consider it.

Errors of omission – deciding not to do something even when the data supports the decision – also have a cost.

Additional reading

U.K. fund manager Baillie Gifford recently wrote a piece on Howdens that is worth reading. You can read it here.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

Disclaimer:

This material is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author or his family may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.

Hello Todd,

First of all, congratulations on this publication and on the initial thesis, both are very good.

There are a couple of risks regarding its international expansion that make me quite skeptical about investing at the moment. Their culture and business model in the UK is beyond doubt, it's extraordinary.

However, sometimes transferring that business model to other countries, no matter how well it works in your home country, might not work. Not all countries follow Howden's business model, where the builder contacts the kitchen supplier directly. In many other countries, the model is the opposite: the end customer contacts the kitchen supplier directly. Look at Copart, it has an extraordinary business model in the USA and UK, yet transferring it to Germany is taking a long time despite the benefits for all involved parties.

Another risk I find important is related to kitchen styles. What works in the UK may not be appreciated in France, Belgium... This will imply having many more kitchen models, materials, suppliers... it's complicated.

Lastly, Howden is not counter-cyclical. If a recession occurs, they might struggle due to their strong ties to the construction sector.

As I mentioned to you on Twitter before you wrote the thesis, I had been studying it for a while. If you want to read it, let me know and I'll give you free access to it.

https://galicianinvestor.substack.com/p/opportunity-in-the-uk

Thank you very much.

Interesting company; look forward to learning more about it. What have you found to be the most efficient way to buy the shares--perhaps on the London exchange? There didn't appear to be much trading activity in the ADRs.