Too Many Professional Managers, Not Enough Stewards

Stewardship is a powerful force in life and in business. Identifying stewards of shareholder capital can increase your odds of finding great businesses with long term value creation potential.

Audio version:

My house is 86 years old. Being a history nerd, I naturally researched its history – even found the original newspaper advertisement - and discovered a half-dozen families that lived here before we did.

Each family raised their kids here, went to their jobs, maintained the house (some better than others), and moved away. Now, it is our family’s turn. Eventually, we will also move out.

While we “own” this house, we are more accurately its stewards. Improvements we make to it will serve us for a time, but they will also benefit whoever comes next. I hope many more families get a chance to enjoy it as much as we do.

In the same spirit, management teams we’re interested in as long-term investors act as stewards of shareholder capital.

What does this mean? It means caring for the institution and believing in its mission and purpose. It means increasing shareholder value not just during their tenure but also setting the company up to continue to increase shareholder value after they’re gone.

In turn, that means tending to and widening the moat. Companies are not static assets like gold or diamonds. The company you bought ten years ago is different from the company it is today.

Acquisitions, divestitures, capital expenditures, R&D, hiring, etc., are all at management’s discretion and can make the company tougher or easier to compete against over time.

The mark of CEO stewardship is how the company performs in the years after they step away.

The excellent book Lessons from the Titans has a great quote from former Honeywell CEO Dave Cote, that nicely sums up this concept. He said, “I want to make money on the stock 10 years after I retire.”*

That’s a stewardship perspective.

What’s more impressive is that Cote’s comment was made to the book’s authors (sell-side analysts) during the first few years of his 15-year tenure at Honeywell, not in the twilight when it’s more natural to grow concerned about legacy.

In other words, Cote was making decisions from the beginning through the lens of “How might this impact the company after I’m gone?”

Of course, every business leader needs to balance short-term and long-term decisions. There’s not much variance in how the short-term is defined – months, quarters, maybe a year – but what’s meant by long-term is less clear.

And it’s in the long term where the value lies.

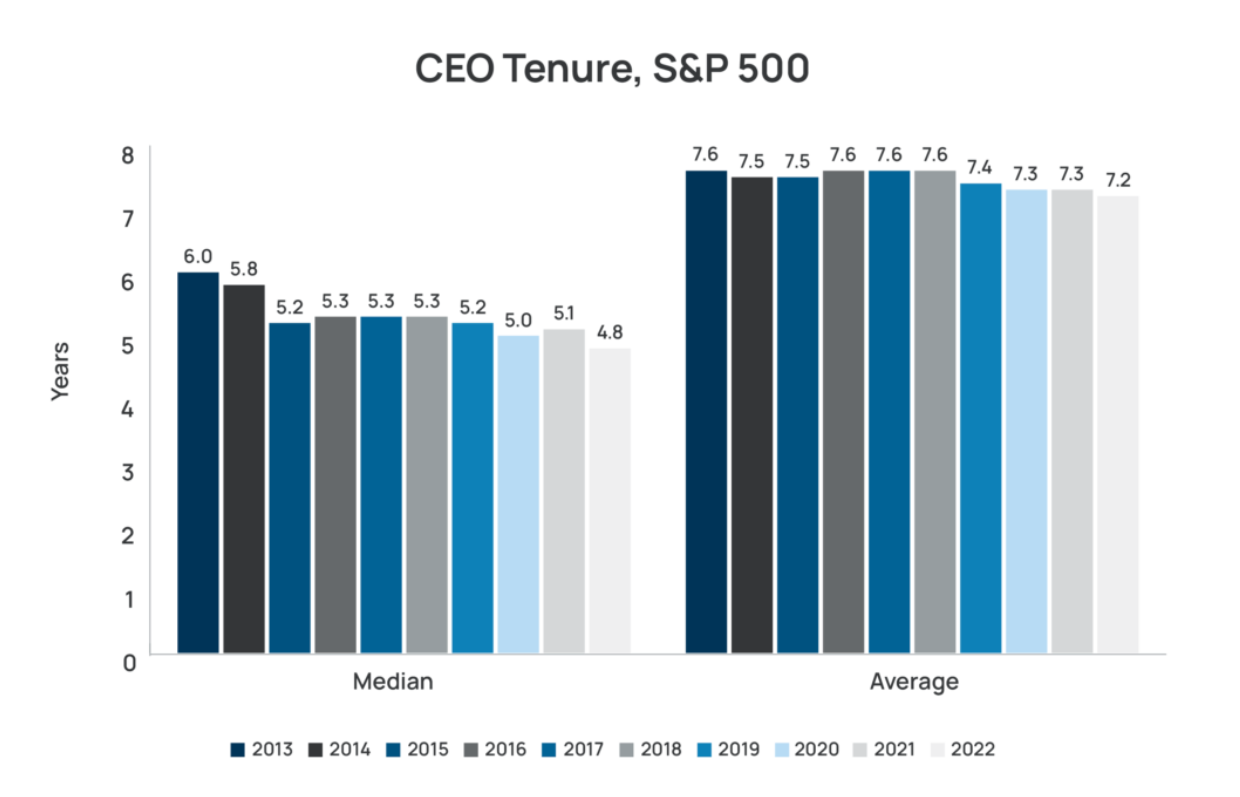

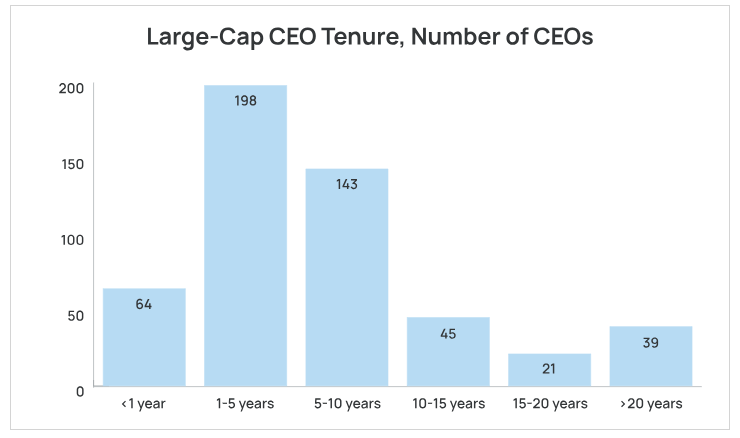

According to Equilar, the median S&P 500 CEO tenure is about five years, and it’s stayed around that level since 2015.

Five years. And then you realize half of the CEOs in the S&P 500 have less than that amount.

It’s unlikely that most CEOs would be able to form a business plan, communicate it to employees, build credibility with stakeholders, and execute that plan to create abundant shareholder value in under five years.

The reasons for such a short tenure are the subject of another post. But if you want a company to compound value over a decade or more, it’s best to avoid companies with revolving doors of professional managers.

There may be a place for professional manager CEOs whose intentions may be good, but it’s best to leave those situations for investors with a shorter timeframe.

Instead, we want to find steward-CEOs who are in it for the long haul and want to leave the company in a position to succeed for years after they retire.

So, how might we begin to identify stewards of capital ahead of time?

Intrinsic motivation – Read and watch as many interviews with the CEO as possible. Check Spotify for podcast interviews, read the local business journal where the company is headquartered, search YouTube videos.

Do you get the impression that they enjoy what they do and believe in the company’s mission?

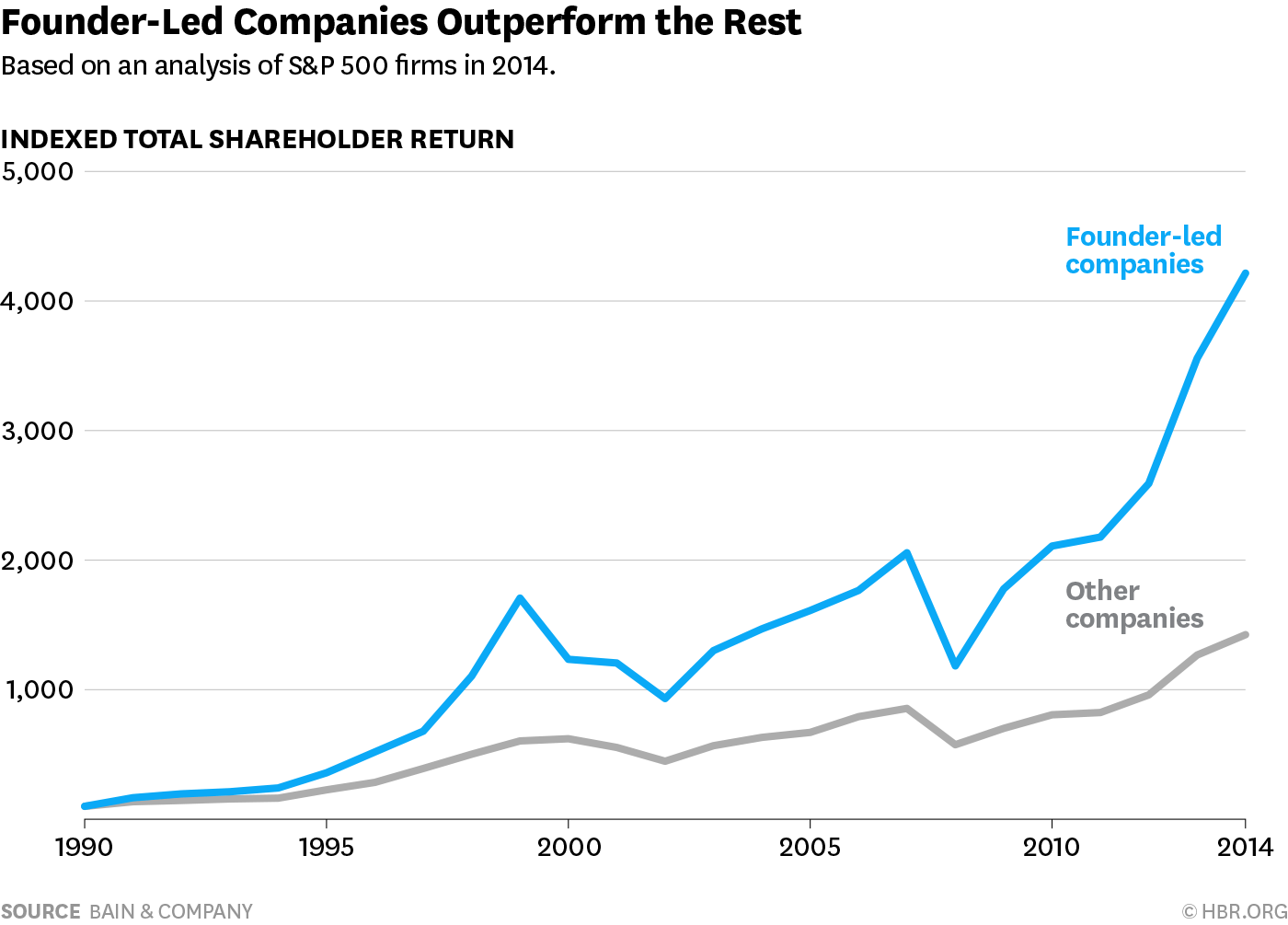

This is one of the reasons that investing in founder-led companies, as a group, has proven an effective strategy. No one has more intrinsic motivation than the person who started the company. When that “founder’s pedigree” is passed down to a hand-picked CEO, there’s a good chance that the successor has intrinsic motivation.

Ownership. If you were running a portfolio where you weren’t sure if your clients would be around next quarter if you underperformed, you would manage the portfolio differently than if you had permanent or otherwise patient capital. Similarly, management’s decisions can be influenced by its shareholder base.

Companies eventually get the shareholders they deserve, so if the focus is on short-term results, that’s the type of shareholder they’ll attract.

Look at the company’s ownership table (found in the proxy and Google searches). Have the top owners changed hands much? Look up some of the top funds holding the stock. Are they traders or are they known for being patient and long-term focused?

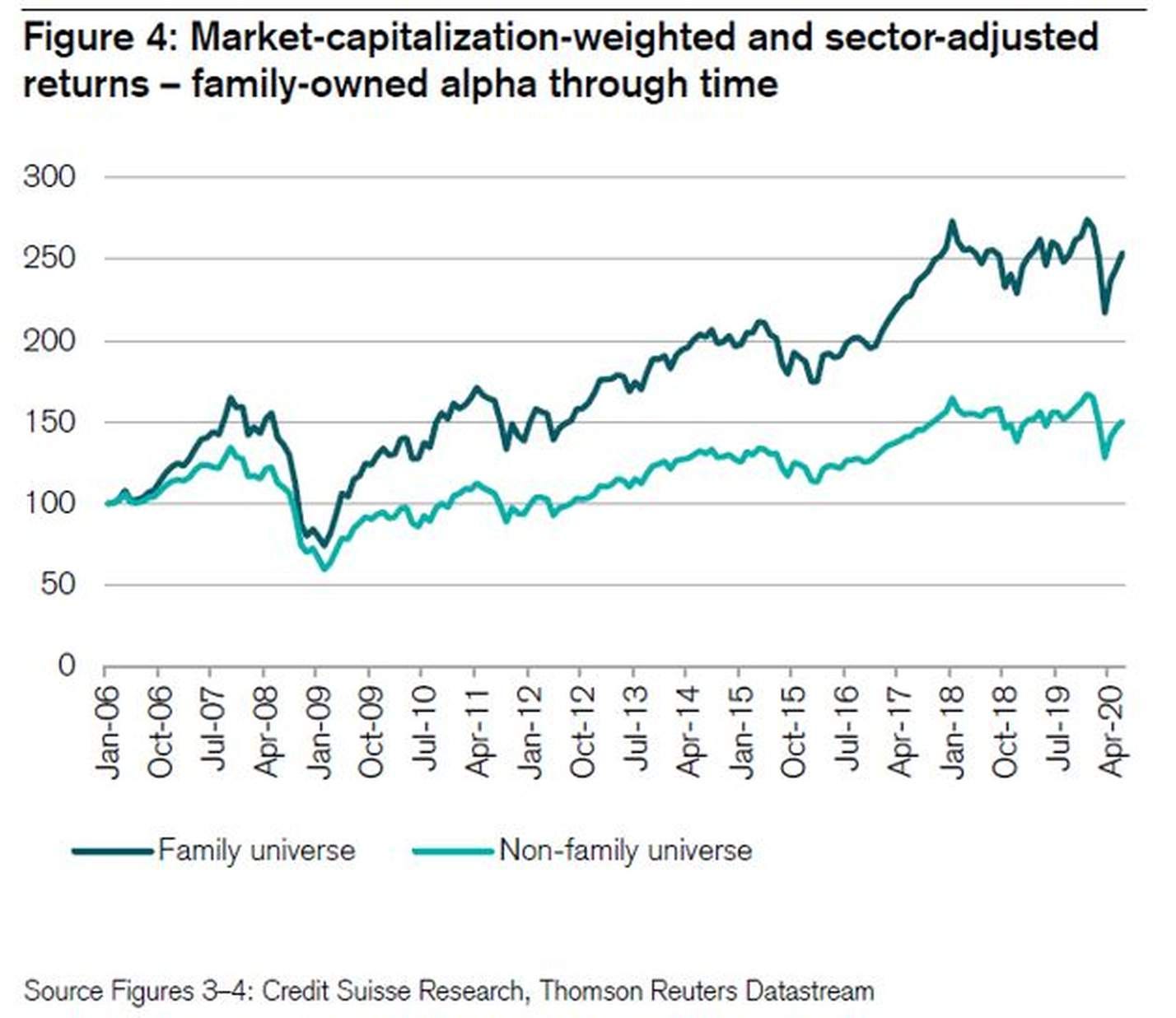

Family businesses tend to play a long game. Companies with material family ownership can provide fertile ground for a CEO to execute their strategy. Similar to founder-led companies, businesses overseen by a large family owner have shown, as a group, to perform well relative to non-family-led companies.

Corporate culture. CEOs set the tone of the company’s culture. Whatever values they emphasize will filter down the ranks to the front-line employees. What messages are they communicating, and how do they relate to the moat?

An example of this is when UK insurer Admiral Group opened its first US insurance operation called Elephant Insurance in 2009. It introduced American employees to its low-cost culture by having employees do a push-up every time they used the printer and handing out monthly cheapskate awards.

Hal Lawton at Tractor Supply has emphasized servant leadership since taking the role in 2020, where customers and employees sit at the top, and he sits at the bottom. This cultural tone matches the company’s objective to “go the country mile” for its customers.

Value vocabulary. Because a good steward of shareholder capital must sustain and widen the moat, the metrics they use to measure progress are noteworthy. The most obvious location to find these metrics is in the company’s annual proxy statement where the board decides which metrics to use to calculate executive bonuses.

If the company is using revenue or EBITDA to measure progress, for example, there’s no clear link to how the company is creating value for shareholders. The further down the income statement – e.g. pretax income, net income, EPS - the more relevant the figure is to shareholders. Even better are cash flow and return on invested capital metrics.

For example, Dave Cote’s bonus metrics at Honeywell were EPS, free cash flow, and working capital turns. They are well-aligned with his long-term objective of setting the company up for future success beyond his tenure.

Final thoughts

When we invest in a company, we’re not just investing in its present economic moat but how it will bear out over the next five, 10 years, and beyond. Management’s decisions over that period will profoundly impact that moat trajectory, for better or worse.

Identifying companies that encourage and attract thoughtful stewards of shareholder capital is paramount to our objective here at Flyover Stocks, and that’s where we’ll focus in the content to come.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

*While Honeywell’s stock has underperformed the S&P 500 since Cote’s retirement, the company is outperforming its peer group of industrial conglomerates.

*At the time of publication, Todd and/or his family owned shares of Admiral Group and Tractor Supply

Disclaimer:

This material is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author or his family may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.

That Honeywell proxy was beautiful to read!