What We Talk About When We Talk About Moats

It's time we get back to the basics

Audio version:

Since at least the 1986 Berkshire Hathaway letter, Warren Buffett has used the phrase “economic moat” to describe a company’s durable competitive advantage.

In classic Buffett fashion, he crafted a simple visual metaphor to communicate a complex and dynamic topic.

While that makes the concept of moats more easily transmittable across a broad population, it’s also resulted in misapplication and overuse by investors and management teams alike.

What I’ll try to do here is get back to what we should be talking about when we talk about economic moats.

Where investors and business leaders start to go wrong with using of the phrase “economic moat” is not defining what they mean by it.

In that 1986 letter, for example, Buffett wrote of GEICO:

“The difference between GEICO’s costs and those of its competitors is a kind of moat that protects a valuable and much-sought-after business castle. No one understands this moat-around-the-castle concept better than Bill Snyder, Chairman of GEICO. He continually widens the moat by driving down costs still more, thereby defending and strengthening the economic franchise.”Here, Buffett defines two essential facets of GEICO’s moat. First, the source of its moat – in this case, a structural cost advantage. And second, describing what it takes for GEICO’s moat to get even wider – i.e. management’s skill at driving down costs.

With that framework, an interested investor can keep tabs on GEICO’s and its peer group’s expense ratios and determine if GEICO’s moat is indeed widening or narrowing. In turn, this can give the investor confidence (or not) in the company’s ability to out-earn its cost of capital in the coming years.

And ultimately, that’s what you want to gain from any conversation about economic moats. Because when the chips are down, and the company is going through a challenging period – which will happen to every company at some point – you can seize on the opportunity if you’re confident in the company’s long-term ability to generate shareholder value.

At a minimum, any discussion about economic moats should address three questions.

· What is the source of the company’s advantage?

· How can we measure the advantage?

· Is the advantage widening or narrowing?

The source of the company’s moat can fall into a few broad categories like network effects, switching costs, low-cost advantages, efficient scale, and intangible assets. A good starting point is to ask yourself, “If I had sufficient capital, what would it take for me to eat into this company’s profits, and how long would it take?”

To illustrate, if you gave me $1 billion to try to compete against Old Dominion Freight Lines, I might be able to find some land to build some service centers (not easy to do with NIMBY/zoning), buy some trucks, staff up, and hire salespeople. Still, building up sufficient volume in my network will take years. I need to earn customer trust, which takes time. Even if I’m doing it the right way – which requires a slow, methodical approach – it will be well over a decade before I could even begin to compete head-to-head with them on national business.

In the meantime, ODFL can also get better and stronger. That’s what a moat offers companies – time. Time to allow management to focus on maximizing the long-term value of the business. We’ll talk about sizing up management in a separate post.

Measuring the moat will vary by company. In the case of GEICO, you could keep track of the expense ratio to measure its cost advantages. For Costco, you can look at Executive Member penetration, membership renewal rates, and spending per member to gauge trends in its relevance to its customers. In turn, that helps you understand Costco’s bargaining power over suppliers. At a luxury goods company, you want to pay attention to trends in gross margin. If gross margins start to slip, they may be going down-market for volume and putting long-term pricing power at risk.

Whichever company you’re looking at, you want to identify (or even create your own) key metrics that you can use to track the company’s moat trend. A good metric will have a direct tie to returns on invested capital (ROIC)

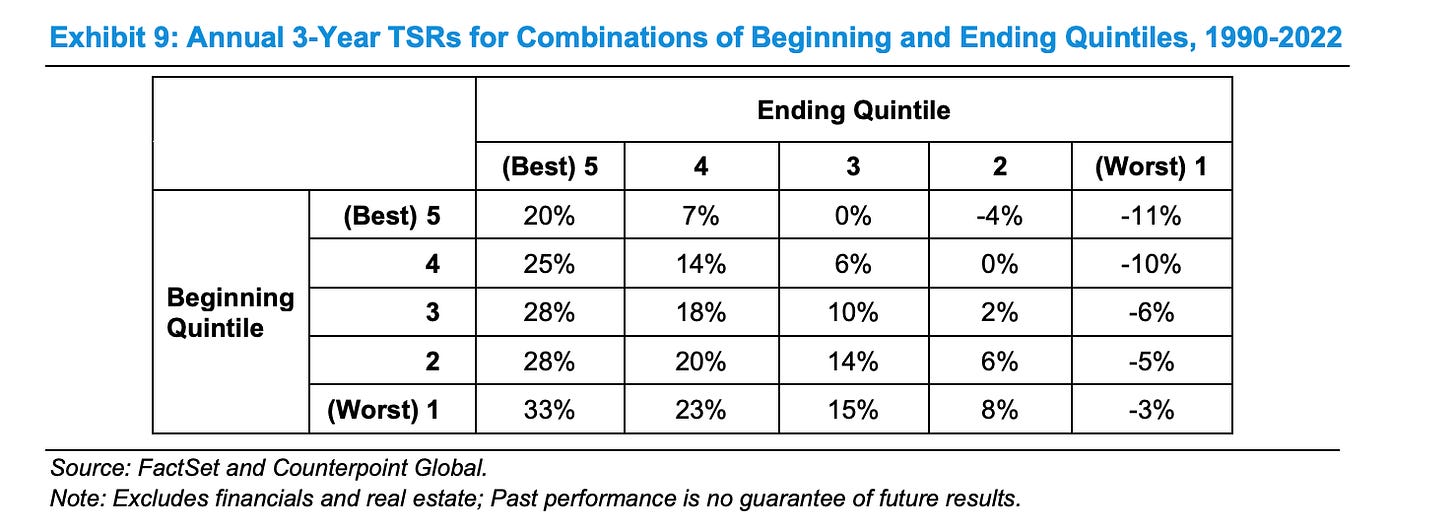

As Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan illustrated in one of their recent papers on ROIC, groups of companies that posted improving ROIC tended to have positive stock returns, and vice versa. For example, in the chart below, companies that started out in the lowest ROIC quintile and ended up in the highest quintile, as a group, had the highest return of any cohort.

Conversely, the table also shows that the worst-performing cohort was companies that started in the highest ROIC quintile and fell to the bottom quintile. (I call these “quality traps” – a topic we’ll also explore later on.)

This makes intuitive sense. A company that started with an 8% ROIC and expanded to 30% ROIC needs to reinvest far less of its cash flow to achieve the same level of growth. The higher ROIC leaves more distributable cash flow for shareholders. As such, the 30% ROIC version of the company should trade with a higher multiple than the 8% ROIC version. The opposite is also true.

Companies with widening economic moats produce higher levels of ROIC or, at the very least, make their current ROIC level more durable than before. Either way, the market should positively adjust its implied expectations around the company’s long-term fundamentals.

Any conversation about moats requires a definition, a way to measure it, and a way to judge its trend. If you or the person you’re speaking with can’t answer those questions, the moat is non-existent or further investigation is necessary. The more we can talk about moats in this way, the more seriously we can take the concept Buffett originally illustrated.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

At the time of publication, Todd and/or his immediate family owned shares of Costco.

Disclaimer:

This material is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author or his family may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.