Economic Moats Explained: What They Are & Why They Matter - Part II

Understanding sources of competitive advantage is the first task of evaluating a company's economic moat

For the second part of this series, we’ll explore the various economic moat sources.

Part I: Why Care About Moats? (free)

Part II: Moat Sources (today’s post)

Part III: Moat Width

Part IV: Moat Depth

Part V: Moat Trend

Part VI: How Management Impacts the Moat

Moats don’t make the company, the company makes the moat. In other words, moats are outputs rather than inputs.

As such, the first step of good moat research is understanding the business at a deep level. Even if you see a company has been able to consistently outearn its cost of capital, the sources of its advantage are not always immediately apparent.

Often, the less obvious the source of the moat, the wider or more durable the moat tends to be. Having a framework for evaluating moat sources can help you identify such exceptional companies more efficiently.

Morningstar’s five moat sources provide a good framework for discussion. They are:

Intangible assets

Switching costs

Network effects

Low-cost production

Efficient scale

We’ll build upon these concepts in the subsequent posts in this series, which address moat width, moat depth, moat trend, and how management impacts the moat.

Intangible assets

Intangible assets is a catch-all for a number of moat sources such as patents, know-how, brands, trademarks, regulatory protection, intellectual property, and culture. Not all of these subgroups are equal in terms of moat value, so it’s important to discern what type of intangible asset moat we’re talking about.

A patent can support a wide moat, for example, but only until it expires and competition is free to create generic versions of the product. On the other hand, a luxury brand can support a wide moat indefinitely - and may even get stronger over time.

Even within brands, you have Veblen goods and those that offer search cost advantages. Demand for Veblen goods increases as the price increase (e.g., luxury brands like Ferrari and Hermes), while demand for a search cost brand (e.g., known consumer brands such as Crest toothpaste or Starbucks) typically decreases as the price increases, albeit at a slower rate than an unbranded commodity product would.

One thing that makes intangible assets so valuable is that they are more likely to produce unexpected value than tangible assets. It’s unlikely, for example, that an industrial machine will yield a result that wasn’t previously considered. A brand, in contrast, can spawn new revenue and profit streams that could not have been considered ex ante and further widen the company’s moat.

Corporate culture hasn’t traditionally been considered in moat analysis, but it belongs in the intangible asset moat source category.

Like any moat source, culture passes the simple test:

Is it difficult to replicate - or even unfair altogether? Yes.

Does it make the company tougher to compete against? Yes.

Buffett touched on this in the 2005 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders:

Every day, in countless ways, the competitive position of each of our businesses grows either weaker or stronger. If we are delighting customers, eliminating unnecessary costs and improving our products and services, we gain strength. But if we treat customers with indifference or tolerate bloat, our businesses will wither. On a daily basis, the effects of our actions are imperceptible; cumulatively, though, their consequences are enormous.

When our long-term competitive position improves as a result of these almost unnoticeable actions, we describe the phenomenon as “widening the moat.”

Delighting customers, eliminating unnecessary costs, and resisting bloat are all fruits of a healthy corporate culture. It’s true that a company with a poor corporate culture can reduce costs, but only for a time.

Indeed, when a great culture is paired with another moat source, good things tend to happen. Intangible assets in general are most valuable when they are paired with another economic moat source.

We’ll touch on that in Part III and IV of this series, but for now, consider how the Deere brand has been used for generations to reinforce and widen its switching cost advantage.

Switching costs

Think about the products and services you and your family use on a regular basis. Some of them - whether it’s Netflix, Spotify, or the Apple ecosystem - become so ingrained in our routines that someone would have to pay us a lot of money to swear them off for the rest of our lives.

This dependence enables the companies to charge higher prices while limiting the risk of customer loss.

And as strong as some business-to-consumer (B2C) switching costs can be, business-to-business (B2B) switching costs can be even stronger. If I’m inconvenienced as a customer, I might be annoyed for a brief period, but an inconvenience for a business could have rippling effects and impact many people.

One of the reasons that Paychex and ADP have been so successful, for example, is that they process payroll and the risk of screwing up employee paychecks during a provider transition is often not enough for a company to justify a switch.

It’s the same thing with Jack Henry, Fiserv, and Fidelity Information Services and core banking services. Deposit gathering is highly competitive and you don’t want to be the bank that upsets its customers during a core banking platform transition, lest you lose depositors that are expensive to acquire.

Service providers like Fastenal, Cintas, and Snap-On have their employees in their customers’ facilities often enough that cutting ties with the company would mean severing personal relationships and potentially disrupting workflows.

Razor-and-blade business models are built upon a desire for switching cost advantages. Gillette is the classic example of this principle - sell the “razor” at a loss to drive product adoption and then sell the blades, which are necessary to operate the razor, at a high margin.

Finally, companies that manufacture products that account for a small percentage of the customer’s costs but provide a mission-critical service have high switching cost advantages.

Rotork, for example, sells and services mission-critical flow control instruments and systems. Approximately 75% of Rotork’s sales come from orders below £100,000; 25% are below £10,000. These tickets are a low percentage of the cost of a massive energy or industrial project where the cost of failure is high. Rotork’s customers would be foolish to switch suppliers to save a few pounds.

Network effects

We discussed the downside of network effects in this post, but as long as the underlying product or service is relevant, network effects are the most difficult moat to attack.

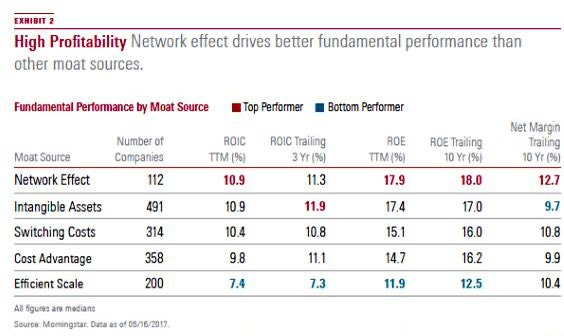

As this research from Morningstar showed, companies that benefitted from the network effect advantage had the highest trailing 10-year return on equity and net margin.

The reason why network effects are so valuable is that, with each incremental user, the platform builds momentum, becomes more valuable, and shuts out substitute offerings as it does. Once you had Facebook, there was no need to have MySpace as well.

Notice that the network effect moat source is also the rarest in the above table. Network effects are hard to establish, not every industry has network effect potential, and they tend to be winner-take-all or winner-take-most industries.

Low-cost production

I’ve found that companies with a relentless focus on lowering costs and diminishing waste tend to be doing something right elsewhere in the business.

My first job was with Vanguard and Jack Bogle’s frugality was at the heart of the company culture. There was a push to lower costs to pass the savings onto the funds’ shareholders.

Sam Walton was cut from the same cloth:

Every time Wal-Mart spends one dollar foolishly, it comes right out of our customers' pockets. Every time we save them a dollar, that puts us one more step ahead of the competition—which is where we always plan to be.

Such a perspective makes a company particularly hard to compete against. All else equal, the company with the lower cost structure can win business by lowering prices or generate higher margins than competitors selling products for the same price. Either way, the lower cost company has the upper hand.

Like any moat source, a low-cost advantage needs to be structural and durable to allow the company to consistently generate ROIC above cost of capital. A company can build a state of the art factory to lower costs, for instance, but if its competitors can do the same within a year or two, the cost advantages from the new factory are temporary and not an economic moat source.

Instead, it’s important to consider how the company might maintain the advantage over the next decade.

Some companies develop a low-cost advantage through deliberate operational practice, but others come by it as a matter of course.

To illustrate, rock quarries and metal beverage can facilities produce low value-to-weight ratio products and can only be transported economically within a certain radius. A rock quarry in California cannot compete with a rock quarry in Florida for a construction job in Georgia.

Efficient scale

The last, and most debatable, moat source is efficient scale. The principle of efficient scale is that a market generates ROICs high enough to attract competition, but low enough to prevent competition from actually entering the market. If the competitor did enter the market, it would drag ROIC below cost of capital for all participants, thus eliminating the incentive to enter the market.

Utilities, railroads, airports, beverage can makers, and other industries benefit from serving limited local markets where large investments in the infrastructure necessary to compete against them present barriers to entry and discourage competition.

Efficient scale can hold for a long time, but unexpected changes in the industry can quickly disrupt the status quo. During COVID, for example, beverage can demand skyrocketed as more people consumed drinks at home. The handful of major can makers like Ball and Crown didn’t have enough capacity to meet demand, so prices rose sharply, which boosted ROIC and made industry entry more attractive.

I wouldn’t want to own a company that showed evidence of efficient scale and no other economic moat sources.

Bottom line

When you boil it down, a good moat source is something that solves a customer’s problem - possibly one they don’t even know they have. Brands can help consumers make easier decisions and save time, switching costs can deepen relationships with customers, network effects more efficiently connect people, and low-cost advantages can save customers’ money.

A company with one economic moat source is already exceptional, but those with more than one moat source are capable of establishing wide moats that enable them to generate ROIC above cost of capital for more than ten years.

We’ll explore this further in the next installment in the series on moat width.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

Todd Wenning is the President and CIO at KNA Capital Management, LLC, which is pending state registration.

Todd can be reached through this contact form.

At the time of publication, Todd, his family, and/or KNA Capital Management owned shares of Berkshire Hathaway.

All information contained herein is provided “as is” and KNA Capital Management, LLC (“KNA”) expressly disclaims making any express or implied warranties with respect to the fitness of the information contained herein for any particular usage, application or purpose. Prior to making any investment decision you should consult with professional financial, legal and tax advisors to determine the appropriateness of the risks associated with such an investment. No assurance can be given that the objectives of a particular investment will be achieved or that an investor will receive a return of all or part of his or her investment. All investments involve the risk of loss, including the loss of principal. In no event shall KNA be responsible or liable for the correctness of any material used herein or for any damage or lost opportunities resulting from the use of such material.

Users of this content may not reproduce, modify, copy, alter in any way, distribute, sell, resell, transmit, transfer, license, assign or publish any information obtained through this website without permission. KNA and the terms, logos, and marks included herein that identify KNA products are proprietary materials. The use of such terms, logos, and marks without the express written consent of KNA is strictly prohibited.

Disclaimer:

Todd is the President and CIO of KNA Capital Management, LLC, an investment management firm based in Cincinnati, Ohio that is currently pending state registration. The information contained on this site as well as kna-capital.com is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as investment advice or as a recommendation of any particular strategy or investment product. This blog should not be considered as a solicitation for services.

This material on FlyoverStocks.com is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author, his family, or KNA Capital Management clients may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

This newsletter does not provide buy or sell recommendations and articles should not be interpreted this way.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Unless otherwise specified, any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.

Flyover Stocks has partnered with Koyfin to provide a discount to Koyfin’s services for Flyover Stocks readers. The W8 Group, LLC, which publishes Flyover Stocks, may receive a commission from a reader’s purchase of products linked from this page as part of an affiliate program.