When 40x P/E is a Bargain

Lessons from a 1992 short-seller attack and the mechanics of "beating the fade"

You may not get what you paid for, but you will pay for what you get. - Maya Angelou

When my wife and I bought our first house 17 years ago, I really wanted a leather couch for the living room. I always liked the way leather couches looked and thought they were a mark of sophistication.

The problem was, I had champagne tastes on a beer budget. As a compromise, I ended up buying a faux-leather couch for half the price. It looked okay – for a while.

With time, the faux leather began to chip and flake, eventually showing large bare spots that we had to cover with blankets when guests came over.

It was a good early lesson in paying up for quality. Had I bought a real leather couch back then, the extra cost would have been covered many years ago in enjoyment and durability.

Companies are not couches, of course. They’re organic. They change. They need to be monitored.

The quality principle, however, is the same. I can forgive myself for overpaying for quality, but overvaluing low quality is a cardinal sin.

Expensive quality

A November 1992 edition of Forbes magazine* featured an article on the industrial distribution company, Fastenal (FAST), which was still in its early growth stage.

The article talked about how Fastenal was a favorite of short sellers, who salivated over the fact that Fastenal traded with a trailing price-to-earnings ratio of 39 times, eight times book value, and over four times revenue. Optically expensive – even by today’s standards.

Forbes added:

“Maybe – maybe – these valuations could be justified if Fastenal were likely to continue its rapid growth. But the shorts contend that Fastenal has already skimmed the cream in many small-town markets. As the company moves into bigger markets, it will encounter more competition from tough operators like Home Depot and Builders Square.”

All reasonable concerns, of course, but ultimately wrong.

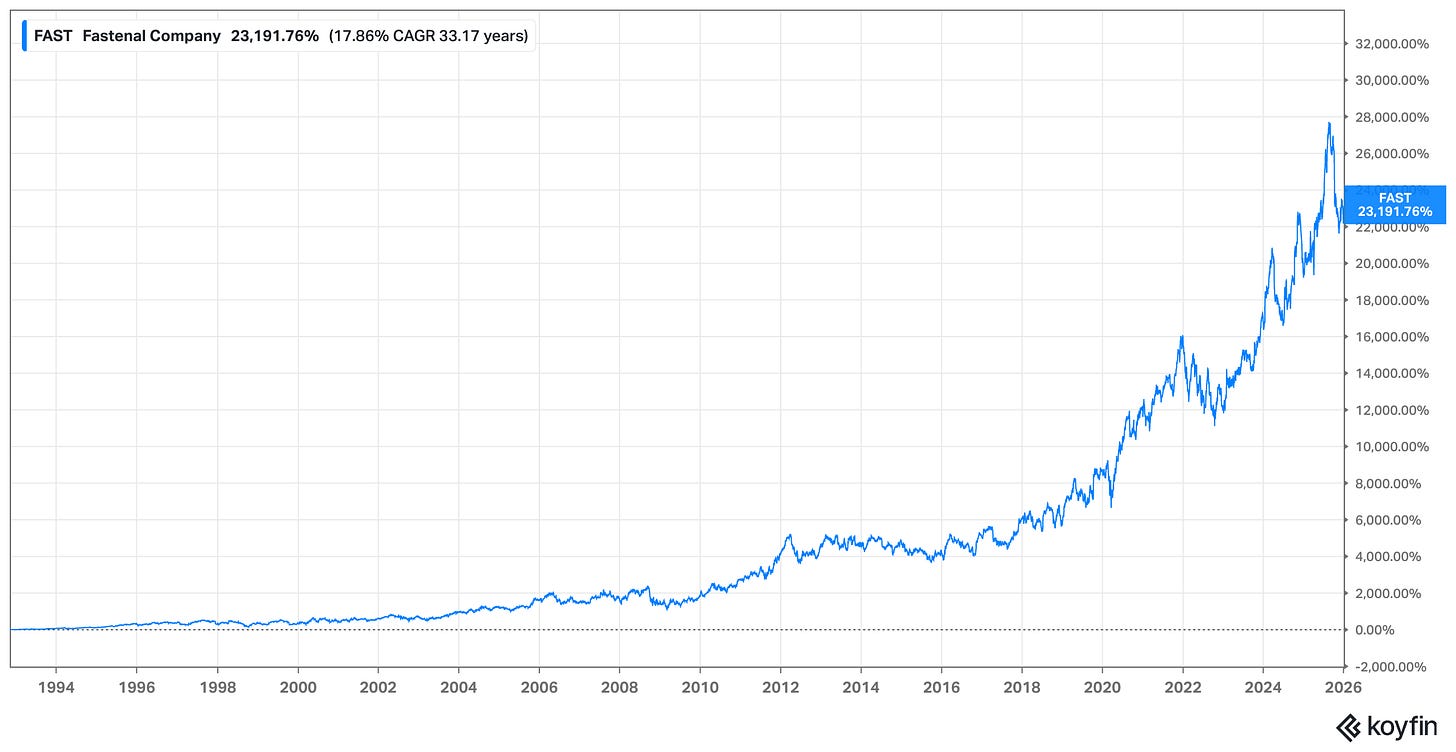

Since the article was published 33 years ago, Fastenal has generated total returns over 23,000%, or about 17.9% compounded annually. Home Depot did fine (13.5% annualized total return), of course, but not as well as Fastenal.

As for Builders Square, which was then owned by K-Mart, it eventually went bankrupt in 1999.

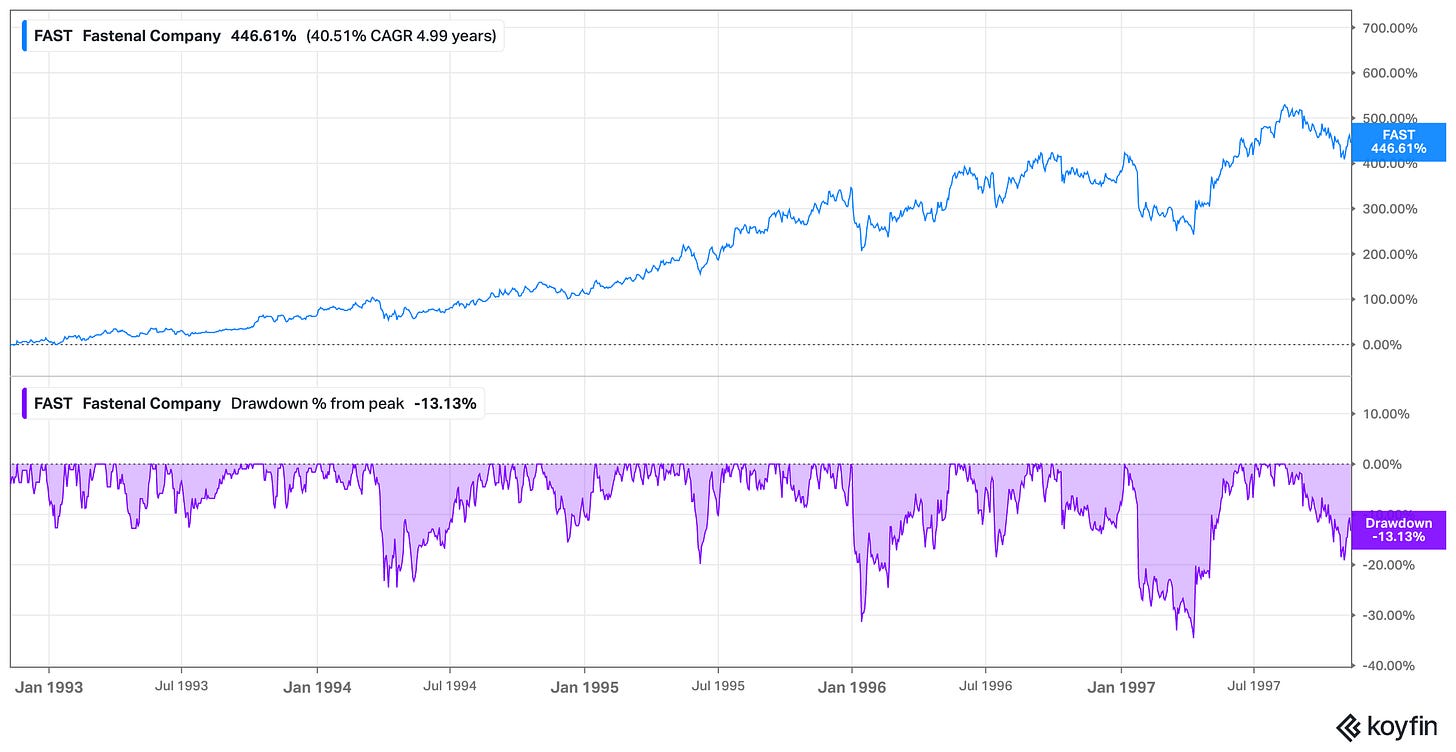

You might reasonably note that a 33 year old chart doesn’t tell the whole story. What happened in the subsequent five years after the post?

Much the same, really.

In the five years following the article, Fastenal did have a few drawdowns along the way, but nothing even close to making a case that the shorts were right in 1992. Fastenal posted 40% annualized total returns over the five year period.

With a P/E of 39 times in 1992, investors were already expecting a lot of growth from Fastenal and the company blew past even those expectations.

The Fastenal example is a good reminder that P/E ratios don’t definitively tell us whether a stock is cheap or expensive. There are 8x P/E stocks today that will prove expensive and 40x P/E stocks that will prove cheap.

Were there signs that Fastenal was a quality company back in 1992?

Yep.

Founder and CEO Bob Kierlin owned 17% of the shares outstanding

Gross margins of 53% were above the industry average of 37%

Fastenal had no debt, and it was self-financing its growth.

While Fastenal’s subsequent performance was not obvious at that point, the seeds of success were planted.

Indeed, in the article, Kierlin provided a blueprint for how CEOs should respond to short attacks:

“I’ve got nothing against short-sellers…They have a role in the marketplace, too. My own portfolio has a couple of short positions. In the long run, the truth will always come out.”

It’s an “alpha move” and a signal of stewardship. Rather than bicker with short-sellers as many in the same situations often do, Kierlin and Fastenal were focused on the fundamentals.

Execute on the fundamentals and create value and the stock price eventually follows.

Beating the fade

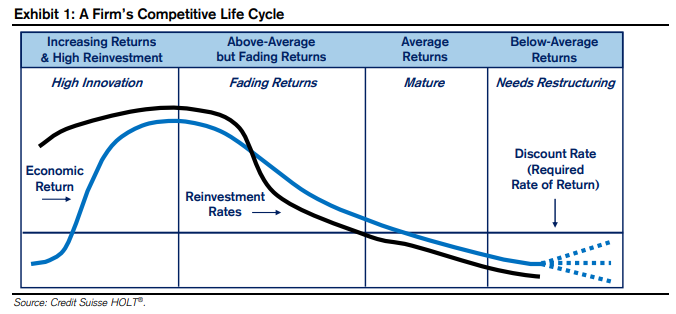

Fastenal’s long-term success is a great example of beating the fade.

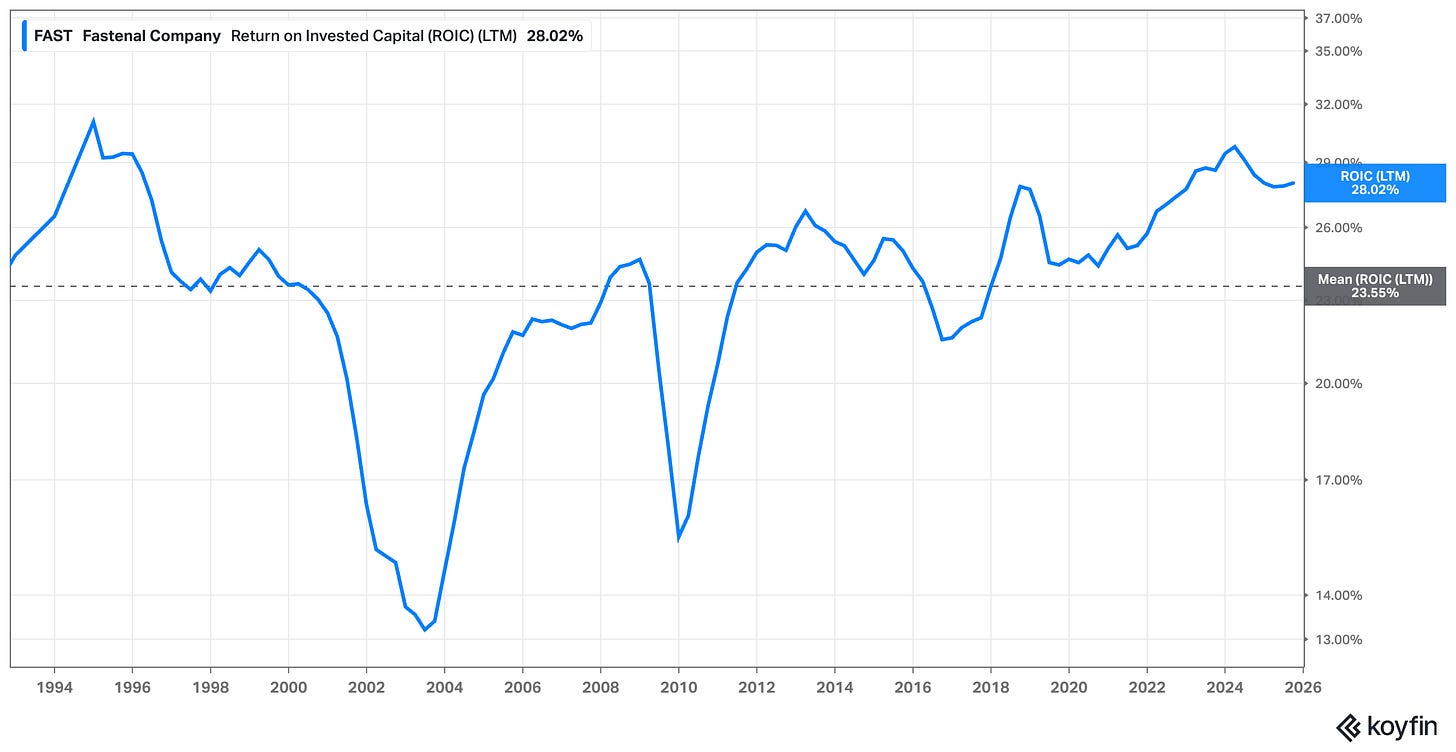

The fade is the implied expectation that the company’s current success and high returns on invested capital (ROIC) will be competed away in the coming years. The fade is priced into every stock to varying degrees.

The short-sellers’ case against Fastenal in 1992 was that its early success would come to an end once it took on Home Depot and Builders Square and that its ROIC would soon fade toward its cost of capital.

Fastenal put those concerns to bed by consistently generating high and persistent ROIC to beat the implied fade. When this occurred, investors had to adjust their expectations higher, which lifted the stock price. (Even when ROIC dipped during the post-dotcom recession, it was above its cost of capital)

To be sure, it’s difficult for most companies to beat the fade, otherwise more companies would outperform.

So how can we begin to identify companies with the best chance of doing so?

While it’s difficult to forecast which companies will be tougher to compete against in 10 years, I think there are some positive signals, which were included in the Fastenal example:

Virtuous corporate culture – everyone rowing in the same direction.

Strong balance sheet – offering resilience in challenging times.

Focus on delighting customers – a happy customer is a recurring customer.

Stewardship mentality – executives who want to leave the company better than they found it.

These attributes are far from guarantees of success, but they provide higher probabilities for success.

Saving money vs. making money

It’s natural for value-minded investors to scoff at high multiples, but whether we buy a stock with an 8x P/E or a 40x P/E, our long-term returns are ultimately determined by the difference between what’s currently priced into the stock and what the company ultimately delivers relative to those expectations.

When we find an item of exceptional quality, we shouldn’t be immediately turned off by the price tag. When we go cheap for cheap’s sake, much like I did with my faux leather couch, our reward is short-lived. We feel good initially because we saved money, but in reality we’ve impaired our long-term outcomes.

The goal isn’t to pay any price; it’s to pay the right price for the right quality. In the long run, the most expensive mistakes we make are paying for cheap things that fail to deliver.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

* ”Bob Kierlin Versus the Shorts” Forbes, November 9, 1992.

Todd Wenning is the founder of KNA Capital Management, LLC, an Ohio-registered investment advisor that manages a concentrated equity strategy and provides other investment-related services.

At the time of publication, Todd, his immediate family, and/or KNA Capital Management, LLC or its clients do not own shares of any company mentioned.

Please see important disclaimers.

Great post! Well done

So right and so helpful to illustrate this, thank you.