Mind the Gap: The Risks of Missing Moat, Management, or Valuation

Some rationalizations when investing can lead to impaired capital

Audio version:

Mind the Gap signs are so ubiquitous in the London Underground that they are printed on mugs and t-shirts for tourists to remember their trip to London fondly.

It’s easy to forget that its message is also quite serious. If you don’t mind where you’re going when you board the train, you may step into the gap between the platform and the train and seriously injure yourself.

Similarly, when approaching a new idea, oblivious investors can seriously impair their capital by missing something important. For quality investors, that means missing the moat, management, or valuation.

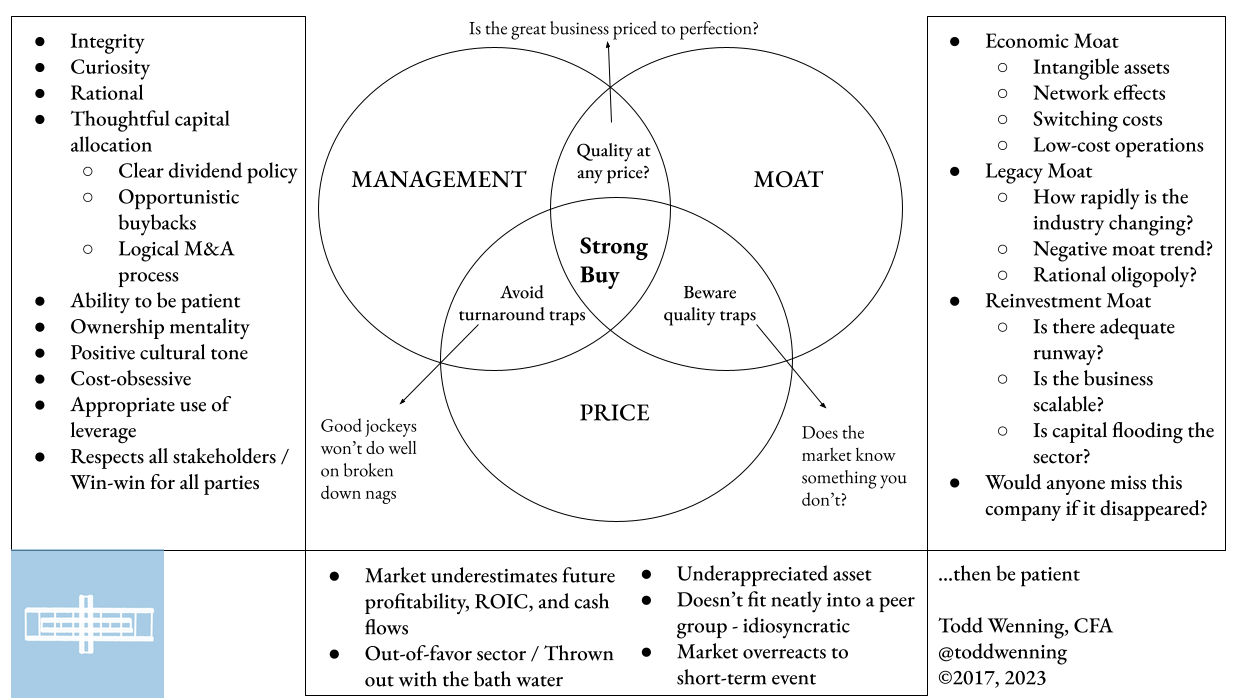

That’s why when I put together my investment philosophy diagram, I made sure to highlight the gaps in the overlapping circles.

These are situations in which only two of the three components were present.

Quality at any Price: Moat + / Management + / Value -

Quality Trap: Moat + / Management - / Value +

Turnaround Trap: Moat - / Management + / Value +

I’ve fallen into all these traps at various points and aim not to make those mistakes again.

Quality at any Price

As consumers, we learn from experience that “you get what you pay for” and “buy cheap, buy twice” are good rules of thumb. A higher-priced item is usually superior in some way to the lower-priced one.

Similarly, quality businesses that are generating high returns on invested capital (ROIC) with attractive growth profiles deservedly trade with premium multiples.

But great companies don’t always make great investments. Sometimes the premium is too dear, making the forward returns muted.

It’s an extreme example, but the following table of March 2000 dotcom darlings (shared on Twitter by @newlowobserver) drives this point home.

Some of these were flops, of course, but Cisco, Oracle, and Qualcomm turned out to be great businesses that posted strong revenue and earnings growth over the subsequent decade. Investors in these companies were so euphoric in March 2000, however, that there was no way they could live up to the expectations, and returns in the following decade were poor.

As we discussed in this earlier post, your return is a function of the dividend yield plus earnings growth (the investment return) and the change in the price-earnings ratio (the speculative return) during the holding period.

Paying too dearly for a great business can lead to poor results. To illustrate, a non-dividend paying company that compounds earnings at 15% per year over five years – a tremendous achievement for any company – would still generate negative returns over the period if the P/E concurrently shrunk from 50 times to 22 times.

To achieve even 9% returns in that scenario, you’d need to assume the P/E would be 38 times in year five. Yes, a great company can maintain that type of premium multiple, but a lot must go right for the company and the markets.

How might we guard against the Quality at any Price trap? Here are three questions we can ask ourselves:

Can you articulate a compelling bear case? You’re not trying to make a case that the company’s moat will vanish or its management will turn out to be frauds, but even slight changes in trajectory can result in a de-rating of the P/E toward the market average. If you can't formulate a thoughtful bear case, you don't have a strong enough bull case. Or at least you don't have enough conviction to hold if sentiment turns negative. And it will at some point.

Would you get unanimous applause from your peers if you announced the investment? As Buffett said in 1979, “You pay a high price in the stock market for a cheery consensus.” Well-known quality businesses naturally attract admiration from other investors, especially when the stock price is moving higher. This sentiment can create a halo effect around the stock. If this happens, take caution.

What are other investors missing? A great business can still have an underappreciated asset. Most investors know that NVR is a high-quality homebuilder, but only a few reports I’ve read mention its network of manufacturing centers across the eastern seaboard that supplied its communities in progress and accelerated inventory turnover.

On the spectrum of celebrating after making an investment and feeling like you’re going to puke, err on the side of the latter. An investment should feel uncomfortable when its made. There should be some uncertainty. When investing with a cheery consensus, your reward comes at the beginning and not in the future, where money gets made.

Quality trap

It’s always a letdown to start researching a company with clear competitive advantages and an optically cheap valuation, only to discover management is ineffective or incompetent as allocators.

Moat erosion begins behind the castle walls, so it’s essential to know who is at the helm.

Companies with wide economic moats can do fine with the proverbial “ham sandwich” in the C-suite for a while, but eventually, that catches up with the business.

When management poorly reinvests capital, ROIC declines faster than it otherwise would have, accelerating the reversion to the mean.

Look, no management team is perfect, just like no investor is perfect. Mistakes happen.

But I want to see thoughtfulness regarding allocation decisions and a sense of stewardship for the company.

To assess capital allocation decisions, I want to understand better what alternative options were available, at which point in the industry cycle the decisions were made, and what valuations looked like at the time of the decision.

In other words, what was the process behind the decisions? Over time and enough iterations, it's the process that determines success or failure.

Regular impairment charges, ill-fitting dividend policies, and ill-timed buybacks and acquisitions are signs that the board and management are not carefully considering capital allocation.

We discussed the importance of stewardship in this article. I'm looking for a sense of responsibility and duty to the company and its stakeholders. Stakeholders – employees especially – pick up on the cultural tone set by management.

When an employee is underpaid and sees her CEO regularly profiled in business magazines or listed as one of the country's top-paid CEOs, she will take notice and adjust her enthusiasm for the place accordingly.

The opposite is also true. When I researched Old Dominion Freight Line, for example, one person I spoke with said they were amazed that someone in upper management knew front-line employees by name. Costco's incoming CEO, Ron Vachris, started his career 40 years ago as a forklift driver. Employees pick up on these vibes, as well, and they reinforce a virtuous corporate culture.

It’s best to stay away if you have a sense that management has a poor capital allocation approach or has poor stakeholder relations. Moats can narrow faster than expected, making forecasting even more difficult.

Turnaround trap

Some of my bigger mistakes as an investor have come from this trap. You’d think high quality managers would go part and parcel with a moaty business. It’s not always the case.

Management can be thoughtful allocators and have a stewardship mentality, and the business can look cheap on paper, but that doesn’t mean it has a moat.

In January 2014, I profiled mattress and furniture textile manufacturer Culp in my “Seeking Small Cap Moats” series. Management, which was (and still is) run by the founding family, had in recent years done a remarkable job fixing its balance sheet, opportunistically repurchased stock, and employed economic value added (EVA) metric in its bonus plan.

I noted in my write-up that it wasn’t clear how or why imports wouldn’t compete with Culp in mattress fabrics (its most profitable business), but the sustained profitability suggested a low-cost advantage was present related to relatively low transportation costs and economies of scale.

To be sure, the stock did well in subsequent years, but by 2018, the competitive landscape changed. Chinese manufacturers indeed started dumping mattress fabric and undercutting Culp on pricing. Other countries have since followed. While the US Department of Commerce has responded by issuing anti-dumping tariffs, the damage appears to have been done on the pricing side.

Hopefully Culp can turn things around, but the case study is a reminder that management can’t be a stand in for a moat, no matter how thoughtful they are about capital allocation or if have a stewardship mentality.

The moat is the engine that creates potential energy, and it’s management’s job to turn it into kinetic energy. Even if you have the management equivalent of Lewis Hamilton at the wheel, there's little they can do with a go-kart engine for a moat.

Avoiding pitfalls

Investors can make money in many ways. You can do well betting on turnaround stories. You can do well with deep value. You can do well with riding momentum stocks, assuming you know when to jump off.

But for quality-minded investors like us, who want to own pieces of great businesses for a long time, all three of these factors must be present.

If you’re going to get one of the three correct, make sure it’s the moat. Bad management can be replaced. Great businesses led by top management can create new revenue streams and earn their premium multiples in ways you didn’t expect.

While this doesn't mean you should ignore or diminish the importance of management or valuation by any means, if you get the moat wrong, everything else falls apart.

It’s rare to find opportunities where all three factors are 10 out of 10. The moat may be a four, management a six, and price an eight. The important thing is that each factor passes a threshold of acceptability to you. At that point, you can put on your portfolio manager hat and establish position sizes that reflect those risks and opportunities.

Above all, you should aim to avoid any company that doesn't pass one of your thresholds for moat, management, or value. No amount of clever portfolio management can fix falling into one of those traps.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

At the time of publication, Todd and/or his immediate family owned shares in Costco

Disclaimer:

This material is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author or his family may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

This newsletter does not provide buy or sell recommendations and articles should not be interpreted this way.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Unless otherwise specified, any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.

Flyover Stocks has partnered with Koyfin to provide a discount to Koyfin’s services for Flyover Stocks readers. The W8 Group, LLC, which publishes Flyover Stocks, may receive a commission from a reader’s purchase of Koyfin services.

It's always a sobering reminder to look at how long it took market darlings to re-reach their highs from past bubbles. Thanks for this piece, Todd.

That Venn diagram, and the questions surrounding it, is spectacular. Thankyou.