Turning of the Tide: Assessing Terminal Value Risks

Terminal value accounts for the bulk of a company's intrinsic value - threats to it should be taken seriously

A noted inventor lately said to me that “The three things to be considered in an invention are: does it save time, does it save money, does it save thinking.” People will accept anything that increases business capacity by an economy of time, any system by which work is done with the required good results and at a cheaper rate is sure of success, and there are people who will pay almost anything to escape thinking, taking the trouble to use their brains themselves. (my emphasis)

What an excellent framework for thinking about innovation. Does it save time, money, or thinking?

It could have been said today by a venture capitalist or during the dot-com boom in the late 1990s.

But it came from a February 1897 article in the Cincinnati Enquirer called “Changes in Road Motors: Practical Results with the Horseless Carriage.”

As a historian, I naturally look toward the past when unsure of what might lie ahead.

Circumstances change, but human behavior, by and large, does not. As Ecclesiastes tells us, “There is nothing new under the sun.”

Investors face several potentially game-changing technologies and innovations that call into question the economic moats of some high-quality businesses we follow.

These include:

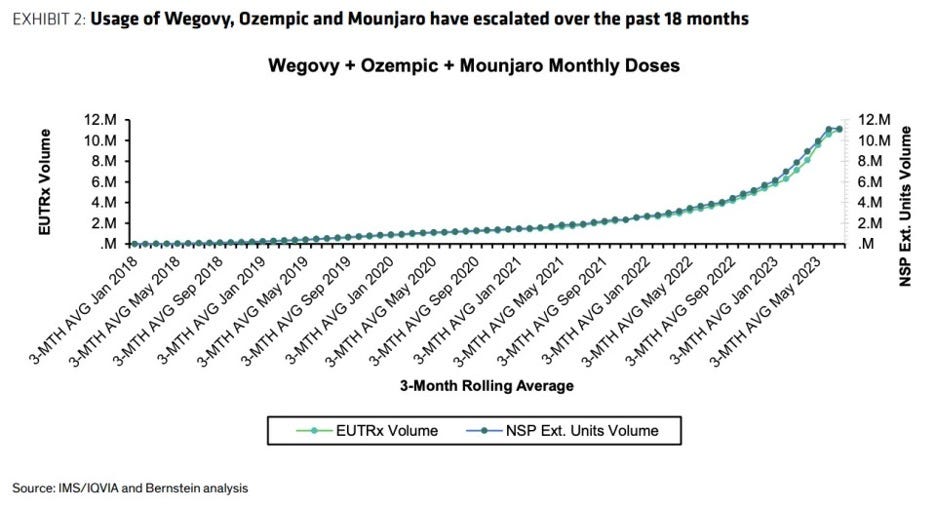

GLP-1 medications like Ozempic and Wegovy, which could significantly reduce food and beverage consumption and healthcare demand.

Expansion of electric vehicles (EV), which challenges the gas station business model and auto parts dealers.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLM), which threaten software and research-based companies.

Autonomous vehicles (AV), which could disrupt the auto repair, insurance, and salvage industry.

Investors should take these risks seriously. In a discounted cash flow model, most of a company’s intrinsic value calculation comes from the terminal, or perpetuity, assumptions. As such, what might happen in 2028, 2033, and beyond ought to be considered.

A particular innovation may not impact a company’s year one or even year two results, but the market will adjust to a new reality as soon as it becomes clear that the long-term trend is negative.

Here’s an example. Though Amazon started selling books online in 1995, bookstores Barnes & Noble and Borders continued to prosper for another decade. Sales didn’t start to decline at either company until 2008.

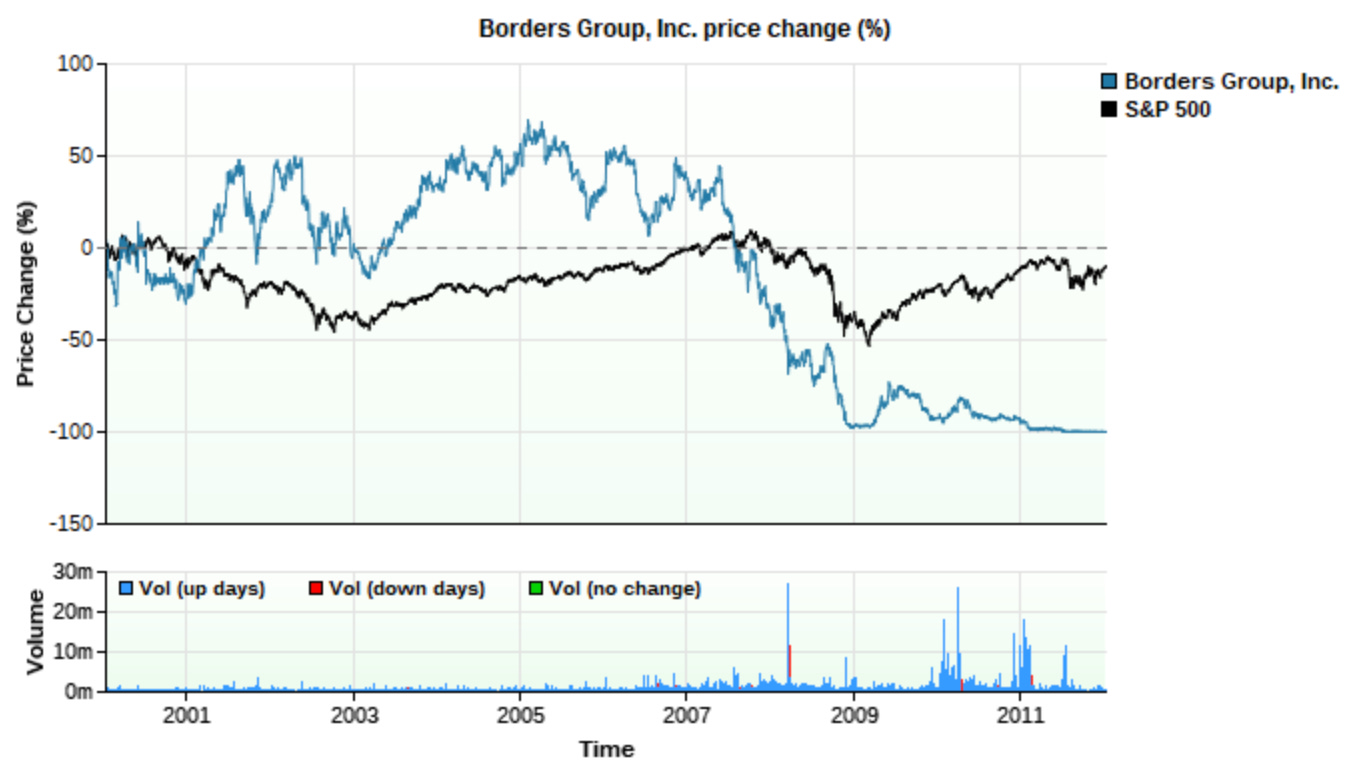

Indeed, had you bought either bookseller’s stock in 2000, you outperformed the S&P 500 for several years before the bottom fell out.

Knowing when to jump off the bookseller train wasn’t easy. It wasn’t a single factor that led to their decline. The combination of the launch of the Kindle e-reader in 2007 and the dawning of the financial crisis didn’t help matters. Even so, some booksellers like WH Smith in the UK navigated the challenges better than Barnes & Noble and Borders.

One of the reasons we so easily recall stories of disrupted companies like Barnes & Noble, Borders, Sears, and Kodak is that they were the exception rather than the rule.

For every disruption story that’s come true, there are many more examples where the new technology flopped, or incumbents were the primary beneficiaries of the technology.

What could go right

Our worries about Kodak-like disruption to our companies are reasonable but stem from loss aversion biases. We feel more pain for each unit lost than satisfaction from the same unit gained, so we are naturally on guard. Each of us has a different loss aversion co-efficient and is thus more or less sensitive to fear of losses.

Let's follow Charlie Munger's advice and "invert" the problem to counter this natural tendency toward loss aversion.

Instead of asking ourselves how a disruptive technology might hurt the company, we should ask how it might help the company.

Take EVs, for instance, and their potential impacts on convenience store economics. As EV penetration increases in the national car parc, recharging will replace refueling with gasoline and will increasingly be done at home.

When recharging is done on the road, however, it takes much longer than refueling with gasoline. That means more time to peruse food and merchandise inside the c-store, where profit margins are much higher than at the pump. C-stores could also add entertainment or leisure activities while recharging occurs.

Buc-cee’s gets it.

The hot topic now is how GLP-1s may reduce demand for food and beverages. Many food and beverage categories follow a "power law" where the top decile of customers accounts for most of the product's demand. Investors are concerned that if customers in the top decile get on a GLP-1, it would negatively impact demand.

That may be true. But we should also consider that most of the big consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies have been around for generations and have come through a challenge or two. It’s worth asking how they might respond to a new trial.

It could come in the form of further product miniaturization done in the name of “portion control” – ahem, shrinkflation – or a shift in advertising tactics.

Over the weekend, JerryCapital on Twitter joked:

Part of the reason this tweet is funny is because we know CPG companies can make adjustments and have done so in the past. Diet soda, anyone?

When evaluating a technological threat to a business, there are two major factors to consider – how potentially disruptive is the technology, and how confident am I that management can make the necessary changes?

Let's start with evaluating the technology. The 1897 article I referenced provides an excellent framework for thinking through important questions. I've included some quotes from the article to illustrate the points.

Is the status quo inefficient?

“That machinery is, humanly speaking, sure, while animal power is always uncertain, is one more weighty reason for pushing on to perfection the construction of the automobile vehicle.”

One of the reasons that digital photography took off was that film was inefficient for the amateur photographer. With a film camera, you snapped a shot that you thought looked good (you had 24 or 36 shots per roll), drove it to a photo store to get processed, and waited at least a day, only to find out that someone had their eyes closed or the film was exposed.

A new technology will gain acceptance if can make someone’s experience more reliable and efficient.

Is the incumbent product expensive?

“In Philadelphia alone there are about 100,000 horses in daily use at a cost of $1 per day, all things considered, such as harness, shoeing, food, shelter, care, loss by death, etc. In other words, it costs Philadelphia $30,000,000 per year to do its traction business by horse power.”

Successful companies with pricing power can mortgage their moat by pressing their pricing advantage too far. This misguided strategy can provide a window for competitors or a new technology to offer better value.

"Cutting the cord" with cable companies took off, partly because it was far cheaper for many customers to self-select the content they valued rather than pay up for increasingly expensive cable packages they did not use. According to a 2017 survey by TiVo, 86.7% of respondents "cut the cord" because of price.

Even though streaming wasn’t a perfect substitute for cable, it was “satisficing” for enough customers to cause a tidal wave of change.

Can my grandmother use it?

“The statement that it will take an engineer to drive a motor vehicle is a mistake. A man who can handle brake and lines and who has enough judgement to guide a horse, will be able to guide the automobile vehicle, where response to the motion of the hand will be instant and precise.”

One of the reasons that the iPhone – and iOS in general - has become so popular is that it just works. You don’t need a degree in information technology to operate it.

The radio only required you to know how to plug something in and turn a dial. Simple.

Products and technologies accessible to everyone are more likely to be disruptive than byzantine ones. This is why cryptocurrencies have (thus far, at least) struggled to gain mass adoption while AI has taken off.

How moats really erode

Let’s say an emerging technology checks off at least one of the boxes above. How does management respond?

Having analyzed moats for over a decade, I’ve come to believe that moats erode from the inside rather than the outside. We hear about how Amazon brought down the mega-bookstores, for example, but that required the mega-bookstores to be unprepared and inflexible in the first place.

An excellent podcast series called Business Wars provides the historical context behind some of the most famous competitive business battles in recent generations. Listen to the multi-part series on Netflix and Blockbuster, for example, and you will learn that Blockbuster had many opportunities to counter Netflix – including buying the upstart for $50 million - but failed to do so.

It's concerning when a cash cow business is at risk, as it can require a hard reset of a company's culture, systems, and incentive structures.

Suppose the board created financial metrics for management, assuming the cash cow remains strong. In that case, the board must revisit those metrics, or management will naturally try to keep the business going.

Similarly, suppose a dividend policy relies on cash flows delivered by the legacy business. In that case, the board needs to revisit the policy, at the risk of alienating shareholders who want the dividend maintained.

In these scenarios, one question is, does the company have a significant off-balance sheet liability?

An example is an overly generous dividend policy that assumed the status quo would persist indefinitely. The board and management would have a problem responding to new threats if it made such a large commitment to its shareholders.

Poor stakeholder relationships are another example. If the company has not treated one or more of its stakeholders – employees, suppliers, etc. – fairly, the affronted stakeholders may be delighted that the company has lost some bargaining power as the new technology arrives.

On-balance sheet liabilities are also an important matter in potentially disruptive situations. All else equal, companies with low debt and or a net cash balance sheet will be more financially flexible to respond to new environments.

Someone has to do it

There's much to consider as we evaluate significant technological changes and the threats and opportunities they present to companies we own or would like to buy.

No amount of analysis will eliminate the risk of disruption – a lot of luck is involved in the outcome, good or bad. Instead, our job as investors and analysts is to get comfortable with the risk probabilities, incorporate different scenarios in our valuation forecasts, and compare those valuations to the current market price.

Let's say that the current market price assumes return on invested capital will regress to cost of capital in three years because of new technology. If we see that as a 20% probability and think there's an 80% chance the company does better than that, that strikes me as an attractive setup.

Of course, we can always control these risks with position sizing, too.

Risks related to emerging technology are complicated scenarios to contemplate and analyze. History provides examples of why certain technologies and innovations gained widespread acceptance.

As the quote at the top of the page suggests, humans will embrace any product that saves them time, money, or mental effort. These tendencies were true of the telephone, the radio, and the internet and will also be true of the next innovations.

Once we determine a technology will take off, we must have sufficient faith in management and the company’s business model to adjust and adapt to the new technology. Otherwise, it’s an easy sell decision.

What do you think? Please let me know in the comments below.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

At the time of publication, Todd and/or his family owned shares of Amazon.

Disclaimer:

This material is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author or his family may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.

I am going to quote you when I write about 1st level thinking vs 2nd level thinking because the Buc-ee insight is awesome!