The Religiosity of the Berkshire AGM, The Downside of Consumer Surplus, and Being Right for the Wrong Reasons

Audio version:

The geographical pilgrimage is the symbolic acting out of an inner journey. The inner journey is the interpolation of the meaning and signs of the outer pilgrimage. One can have one without the other. It is best to have both. - Thomas Merton

The Religiosity of the Berkshire AGM

While attending my first Berkshire Hathaway AGM in 2015, I thought it felt like a religious revival. People were there from all walks of life (the guy sitting behind me was a millionaire farmer in overalls who had invested in Berkshire decades ago), had philosophical common ground, and were in a positive, festive mood.

Having traveled to Omaha a half-dozen times for the AGM (I unfortunately missed it this year), I can say that my initial impression wasn't far off: there’s scripture, prophets, evangelists, ascetics (who only read 10-Ks), rituals, and fellowship. Attendees regularly refer to their trip as a "pilgrimage."

Some consider this concerning, cult-like behavior that can create a herd mentality among quality-minded investors. Indeed, Munger called his followers “groupies” at a Daily Journal meeting.

I can appreciate the skepticism, and some of it is warranted, but one way to think about the "religiosity" of the AGM is that it is the medium by which business and investing virtues are instilled and reinforced, then taken back to be employed at home. Neither Buffett nor Munger set out to make the AGM into a tent revival, but they didn't shy away from it, either.

Religiosity is a powerful yet delicate medium accelerating the spread of an underlying philosophy or belief system. It can be used for good or ill.

This religiosity of the Berkshire AGM doesn't strike me as concerning when you consider the messages being spread are virtues like patience, discipline, fair dealing, frugality, and learning. Consider the business and investing vices that don't occur because of the wisdom shared by Buffett and Munger over the years and reinforced at the AGM.

A friend once told me that he was comfortable leaving his laptop on his seat in the arena while he grabbed food at the concession stand. You wouldn’t do this at most events with 40,000 strangers. No one at the Berkshire AGM wants to be known as the laptop thief. That’s instant excommunication, after all.

The aura around Berkshire and Warren and Charlie might have been the reason for your first visit to Omaha, but you go back to see friends from around the globe who go back each year and, like you, are eager to learn and be inspired for the year ahead.

I don't know what the future holds for the AGM, but it has been a force for good in the investing world and beyond.

Consumer Surplus

One of the hard lessons I've learned in recent years is that companies that delight customers may not be great businesses.

The companies that spring to mind are/were known to go above and beyond for their customers, and their customers rewarded them with strong loyalty. Loyalty is a good thing in itself, but it can create an off-balance sheet (and sometimes on-balance sheet) liability when the companies provide too much consumer surplus to obtain this loyalty.

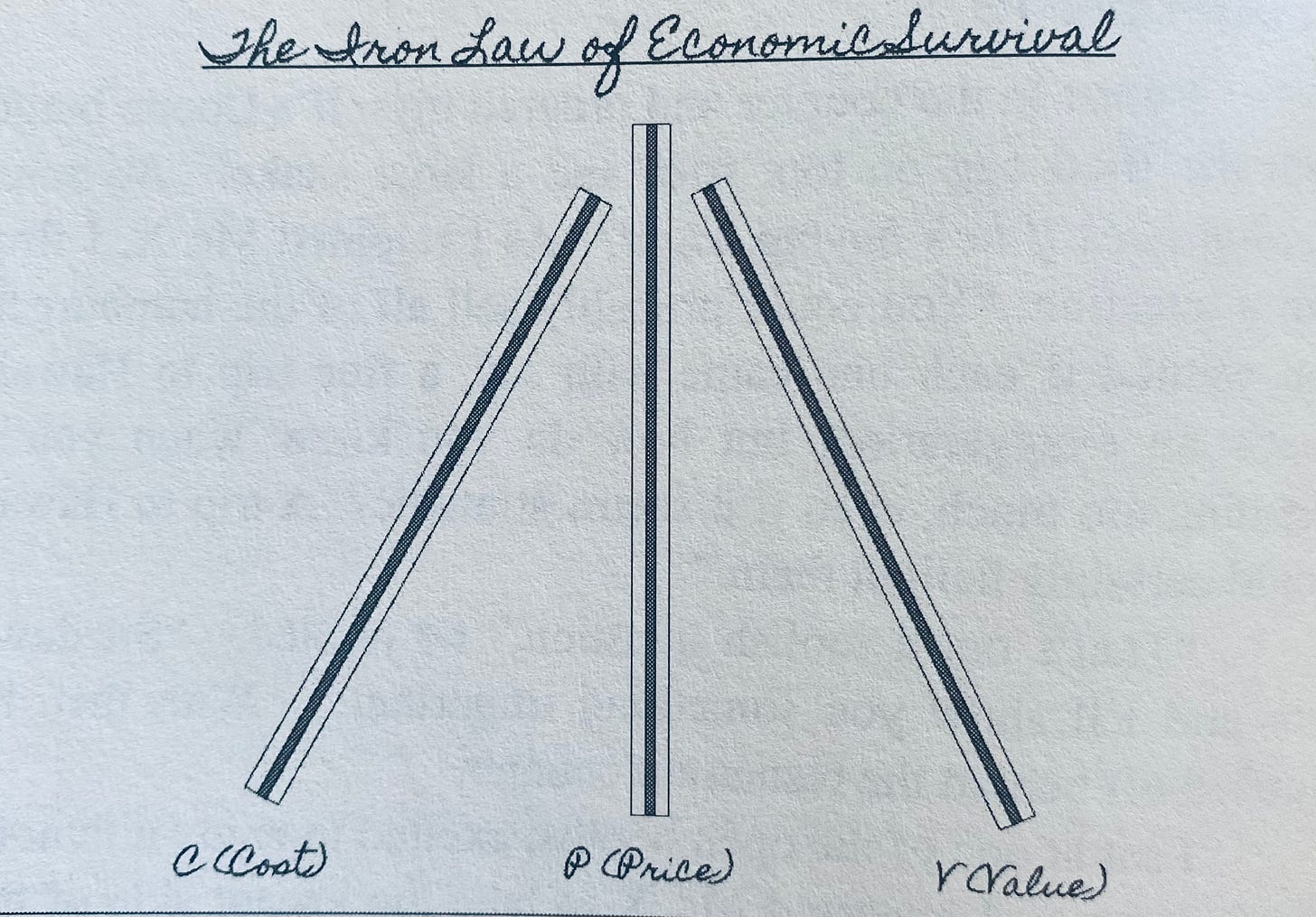

In his novel, The Rebel Allocator, Jake Taylor illustrates the concept of price-value-cost using three straws. A healthy business will provide customer value that exceeds the price of the good; the price of the good, in turn, exceeds the cost. The spread between value and price is "brand," and the spread between price and cost is "profit."

Companies that delight customers and have a sustainable business model can maintain or ideally widen the spread between value and price and maintain or widen the spread between price and cost.

Costco, for example, has improved the value of membership while holding costs at bay through strengthening bargaining power with suppliers. Ferrari can raise prices to offset rising costs because the product's value grows due to scarcity and increased demand.

What doesn't work is when the customer value can’t be pushed any further, and the company needs to raise prices to counter rising costs. In this situation, companies who built their businesses on delighting customers through consumer surplus are usually reluctant to raise prices as it shrinks the gap between value and price. This risks alienating the customer and would lead to attrition and lower revenue.

Delighting the customer can also be expensive and lead to bloated expenses. Shrinking the consumer surplus and losing customers exacerbates the problem.

Yes, companies should want happy customers, but the ultimate goal of a business is to create value. If too much of that value is funneled to one stakeholder - in this case, customers - it isn't sustainable. Companies that forget this will not prove to be good long-term investments.

Being Right for the Wrong Reasons

A company's historical record may tell us something about its quality and durability, but companies are not static assets. They are getting stronger or weaker over time. From a valuation standpoint, the only thing that matters is how the business will fare in the years ahead relative to current expectations.

I've thought about this as I've revisited Starbucks after the recent selloff. It's a company I've owned and covered over the years.

I'm often tempted to buy into fallen angel situations like this for behavioral rather than analytical reasons. Investors are overreacting to short-term headwinds, the thinking goes, and aren't thinking clearly. Once the dust settles, multiples will re-rate higher.

But what if investors are thinking clearly and the selloff is justified?

Behavioral opportunities are more likely to occur in market-wide selloffs than company-specific ones. In the latter case, you need to know why the market is wrong about the perceived idiosyncratic risk. That requires behavioral and analytical insights.

It's possible, for example, that Starbucks' offerings will not be as relevant a decade from now as they are today. Increased competition in the US and high labor costs may crimp margins as consumers finally resist price increases.

On the other hand, behind-the-counter automation may enable Starbucks to cut labor costs and serve customers more efficiently, allowing the company to support margins and drive store traffic.

Starbucks may prove an opportunistic buy today, but basing your thesis solely on being a contrarian to investor sentiment is the wrong justification. Even if Starbucks does well, you'll be right for the wrong reasons. You also need a differentiated business analysis.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

At the time of publication, Todd and/or his family owned shares of Berkshire Hathaway and Costco.

Disclaimer:

This material is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author or his family may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

This newsletter does not provide buy or sell recommendations and articles should not be interpreted this way.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Unless otherwise specified, any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.

Flyover Stocks has partnered with Koyfin to provide a discount to Koyfin’s services for Flyover Stocks readers. The W8 Group, LLC, which publishes Flyover Stocks, may receive a commission from a reader’s purchase of products linked from this page as part of an affiliate program.

I like the "ascetics" concept ;-)

To fully understand Starbucks, and other global businesses, you need to include a rigorous analysis of the Chinese consumer, supply chain and local competition. There are increasingly more coffee options in China that are much cheaper and just as good tasting. It will be harder and harder for Starbucks to defend its moat in that market.