Moats, Money, and Management's Mettle

Timeless lessons on evaluating business resilience

We just got back to Cincinnati from a brief vacation visiting family in Charleston, South Carolina. Every time I visit Charleston, I feel like I’m just scratching the surface of the local history, food, and culture. If you visit Charleston, check out Rodney Scott’s BBQ for the best hush puppies (for the uninitiated, that’s fried cornmeal batter) on the planet.

On this trip, my son (10) and I took the morning ferry to Fort Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired. One of the unanticipated perks of taking the first boat was being part of the group that raised the American flag - 33 stars for the number of states in 1861 - over the fort for the day.

It was a powerful moment on a number of fronts, but I particularly appreciated the National Park Service ranger’s story about the U.S. flag representing the Constitution and how it has proven resilient over 236 years despite many challenges, including the existential crisis that started on that site. One of the reasons for its resilience, the ranger stressed, is the fact that it’s a living document, open to interpretation and change.

Resilience is a theme I wanted to dive into in this weekend’s post.

Read the most recent Flyover Stock company profile

Paid subscribers get full access to the report, including an analysis of the company’s economic moat, management, and valuation.

Moats, Money, and Management's Mettle

“When I analysed the stocks that have lost me the most money, about two-thirds of the time it was due to weak balance sheets. You have to have your eyes open to the fact that if you are buying a company with a weak balance sheet and something changes, then that’s when you are going to be most exposed as a shareholder.” - Anthony Bolton

I’m re-reading the copy of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin which I first read as a history major at Saint Joseph’s University 25 years ago.

One of my new highlights was the following story Franklin told about a printer competitor in Philadelphia named David Harry:

“I was at first apprehensive of a powerful Rival in Harry, as his Friends were very able, & had a good deal of Interest [social capital]. I therefore propos’d a Partnership to him; which he, fortunately for me, rejected with Scorn. He was very proud, dress’d like a Gentleman, liv’d expensively, took much Diversion & Pleasure abroad, ran in debt, & neglected his Business, upon which all Business left him.”

Franklin tells the story of Harry to emphasize the importance of virtue and frugality in business. Harry had all the tools, experience, and social connections to whittle away at Franklin’s success (which was considerable as it included a monopoly on printing Pennsylvania’s new paper currency). As Franklin noted, at the start he would have rather partnered with Harry than competed against him.

Yet Harry failed miserably. Why?

What caused Harry’s downfall, Franklin argues, was an extravagant personal lifestyle, a lack of focus, and inattention to the business’s finances. His business was primed for success, but it fell apart because of character flaws and poor financial management.

While there are clear differences between modern corporations and colonial Philadelphia printing shops, this story reminded me that a business may appear to be strong on the surface - impressive management credentials, an enviable competitive position, etc. - but may in fact be rotting from within without prudent management and a healthy culture.

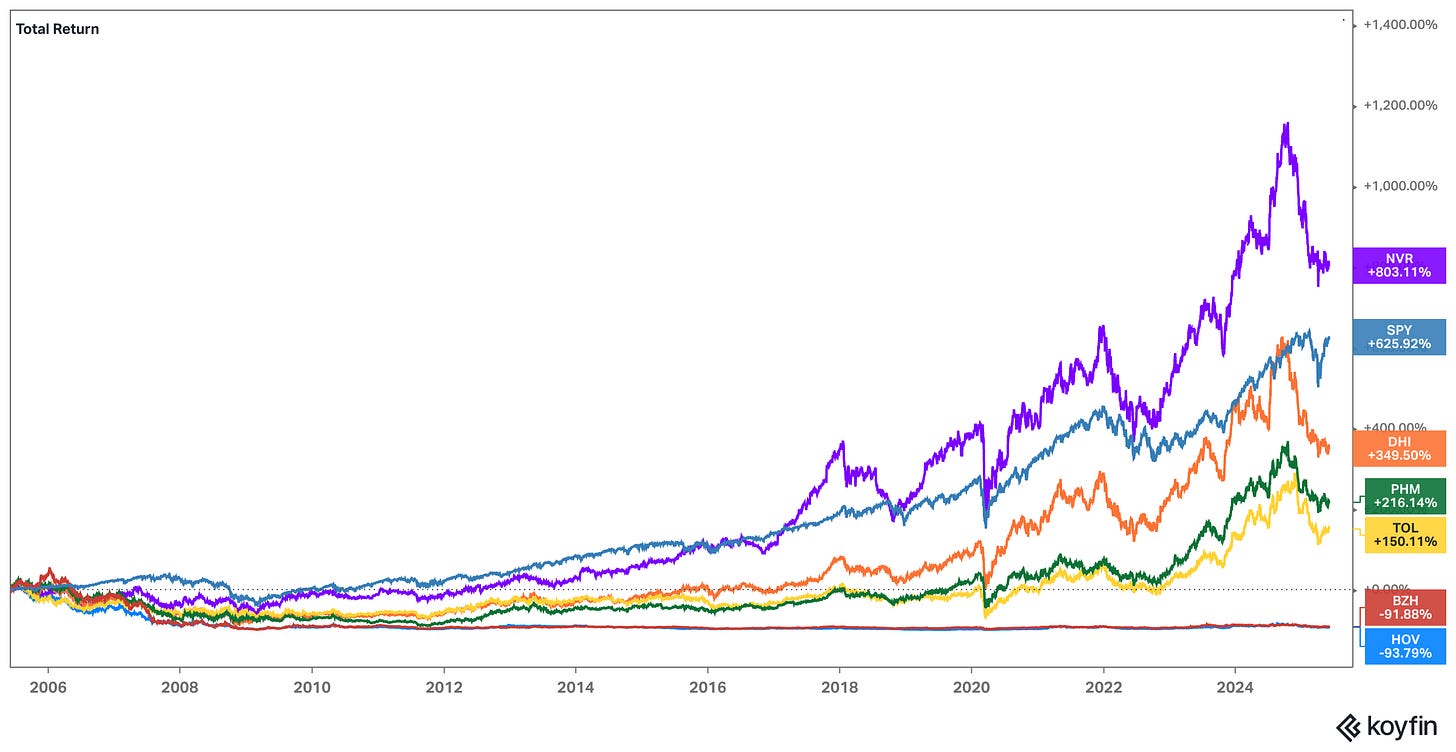

When I put together the Venn diagram of my investment philosophy, I wanted to illustrate the interdependence between moat and management. I don’t think the proverbial “ham sandwich” can run great business for long, nor do I think great management teams can reliably fix no-moat businesses.

Instead, moats provide management teams with time to respond and implement their strategy and great management teams use that time to further widen the moat.

As such, it’s critical to be on guard for signs of moat erosion and management weakness, which are often linked.

Moat erosion starts behind the castle walls. After-the-fact analysis of failed moats (e.g. Research in Motion vs. Apple, Blockbuster vs. Netflix) tends to focus on external disruption - what other companies did to cause the demise - because these are the easiest effects to observe and connect to the outcome.

The opportunity for the disruption, however, is spawned from the target company’s unwillingness or inability to respond - proactively or reactively - to change. As such, it’s critical for investors to understand the company’s culture and management’s character.

Make no mistake: culture and character evaluation is hard. Relevant and reliable information can be hard to come by. This type of analysis is qualitative and subjective, which can lead to biases clouding your judgement.

In my experience, you get a clearer picture of culture and character over time. Measuring management’s mettle during challenges, seeing how they respond in good times, and learning from former employees and competitors can help you get closer to a 360-degree view of the company.

But waiting and following a company for years is of little benefit to an investor hoping to size up a company’s culture and character aiming to make an investment in the coming weeks or months.

There are a few factors that can help you identify potential yellow and red flags.

Balance sheet health

Morgan Housel observed that “As debt increases, you narrow the range of outcomes you can endure in life.” This is true in our personal lives, of course, but also in business. Companies that carry too much debt have limited options and less ability to respond to change.

Because bond payments are contractual obligations, companies have to make their interest and principal payments or risk default. Companies unburdened by these financial obligations are better placed to adapt.

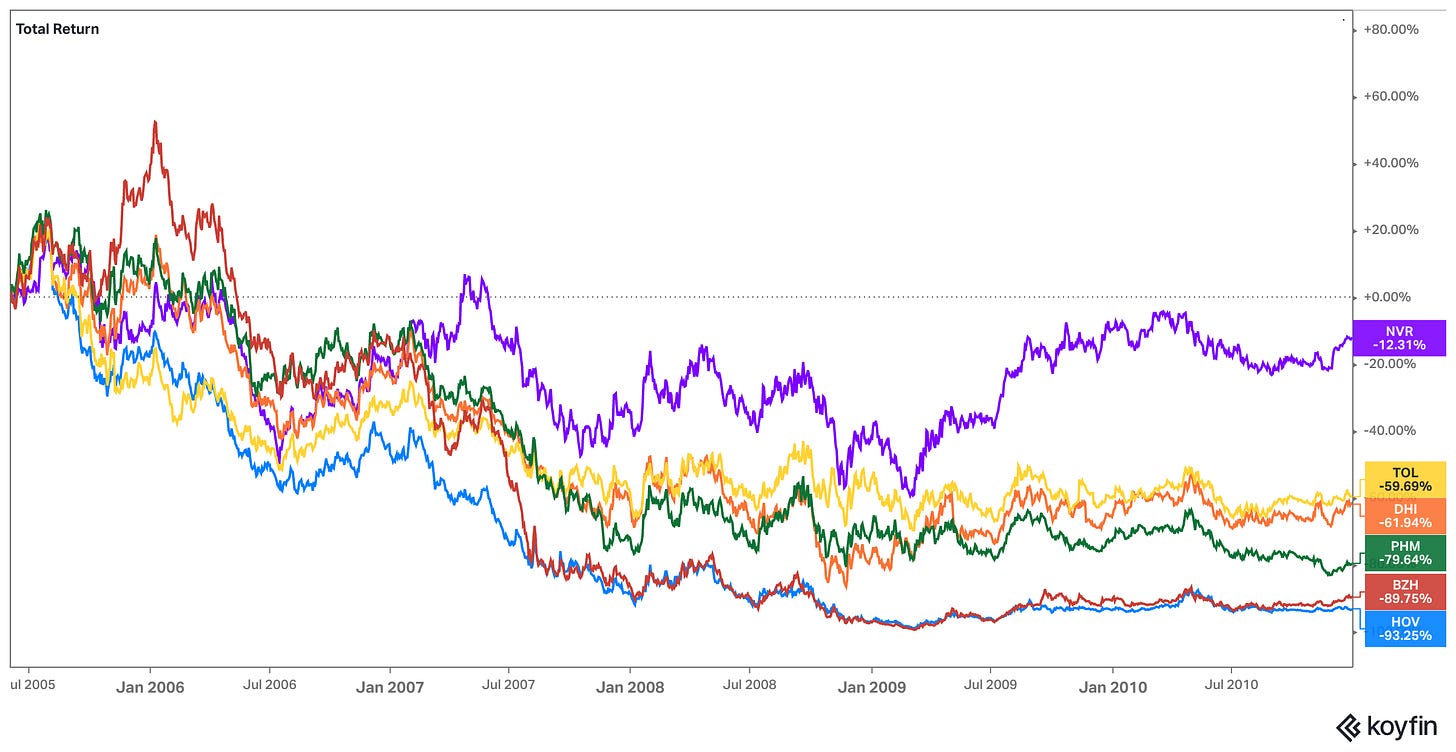

A great example of this dynamic can be found among public homebuilders during the U.S. housing crisis of 2007 to 2010. Most public homebuilders’ business models were based on extensive land ownership, which was usually financed with debt.

Homebuilder NVR, which declared Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1992, pursued a different model when it re-emerged that was “land light” and low debt. This approach served the company well when the housing market collapsed. It picked up market share while its major competitors were in distress.

As shown above, NVR’s stock price held up relatively well during the housing crisis and is the only one of the major homebuilders listed below to outperform the S&P 500 on a total return basis over the last 20 years.

At the most recent Berkshire Hathaway meeting, Warren Buffett stressed the importance of studying balance sheets while building your understanding of the business:

It’s one thing we’ve really never talked about here, but I spend more time looking at balance sheets than I do income statements. Wall Street doesn’t pay much attention to balance sheets, but I like to look at balance sheets over an 8 or 10 year period before I even look at the income account because there are certain things it’s harder to hide or play games with on the balance sheet than with the income statement.

Neither one gives you the total answer on anything, but you should understand what the figures are saying and what they don’t say and what they can’t say and what the management would like them to say that the auditors wouldn’t like them to say. You learn more from balance sheets in my view than most people give them credit for.

You don’t need to be a forensic accountant to identify potentially limiting balance sheet arrangements. As the homebuilder example above showed, the more cyclical the industry, the less debt a business should carry. If a management team of a cyclical business is loading up on debt, they’re unlikely to be playing a long-term game and will have fewer options if the cycle turns against them. It’s best to steer clear.

Multiple generations of family ownership

All else equal, I like to see an ownership link with the founding family, but this can be a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, founding family members can serve as long-term stewards for the business through their influence and board representation. They can serve as a check on ambitious executives who might steer the company in a bad direction and keep management focused on the long-term rather than on quarterly results.

On the other hand, the further removed the business becomes from the first or second generation of family leaders, there’s an increased risk that their descendants place too much emphasis on legacy and not enough on innovation, particularly in periods of change. The fourth or fifth generation live comfortably on their dividends and are not incentivized to rock the boat, even if it’s good for the company in the long run.

Perquisites

A look through the proxy statement can reveal some executive benefits that have no clear link to shareholder value.

Company-owned aircraft, covering spousal and family travel, country club memberships, car expenses, etc. are all yellow flags that management’s focus is not fully on maximizing shareholder value. There are exceptions, but I find it unpalatable when an executive is making millions but has the company paying for their car or their family’s vacation transportation.

Critically, the rank-and-file employees pick up on the tone set at the top. If the executives fly private and stay at five-star hotels on the company dime, do you think the mid-level manager is going to think twice about an upgrade on their flights and hotels?

These costs add up over time and can put the company at a competitive disadvantage.

Timeless lessons

As Franklin observed 300 years ago, virtue and financial discipline are critical factors in business success. These lessons remain true today. No matter how talented the management team or how wide the moat is, the castle can crumble is the financial foundation is weak, the culture becomes corrupted, or management becomes complacent.

As long-term investors, our job is not just to consider the financials and run a valuation model. We also need to make qualitative judgements about the character and culture of our businesses and the people that lead them. If we don’t, we’re more likely to miss warning signs of an eroding moat and a tailspin that’s hard to overcome.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

Todd Wenning is the founder of KNA Capital Management, LLC, an Ohio-registered investment advisor that manages a concentrated equity strategy and provides other investment-related services.

At the time of publication, Todd, his immediate family, KNA Capital Management, LLC and/or its clients owned shares of Apple and Berkshire Hathaway.

Please see important disclaimers.

The story about Franklin’s competitor felt way too familiar. I’ve met people like that,smart, well-connected, tons of potential,but they burn out fast because they’re too busy showing off to actually run the business right.

Also totally agree on the perks part. If the top people are spending company money like it’s personal cash, it sets the tone for everyone else. I’ve seen that happen even in small teams. People pick up on that stuff real quick.

Quick question though. When you’re looking at a company from the outside, how do you even tell if the culture’s solid? It’s not like they advertise bad habits. Are there little signs you look for that give it away?

Safety first!

"Shareholders make money off the income statement, but they survive off the balance sheet”

-Edgar Wachenheim