How to Value "Exceptional" Businesses (And Why Most Investors Sell Them Too Soon)

Value discipline for an outlier world.

Todd Wenning is the founder of KNA Capital Management, LLC, an Ohio-registered investment advisor that manages a concentrated equity strategy and provides other investment-related services.

At the time of publication, Todd, his immediate family, and/or KNA Capital Management, LLC or its clients do not own shares of any company mentioned.

Please see important disclaimers.

“The moment you doubt whether you can fly, you cease for ever to be able to do it.” - J.M. Barrie, Peter Pan

Last week’s article on Fastenal’s stock being cheap at 39x earnings back in 1992 proved to be a popular one.

Perhaps that was due to investors struggling with high multiples in the current market. I know I am.

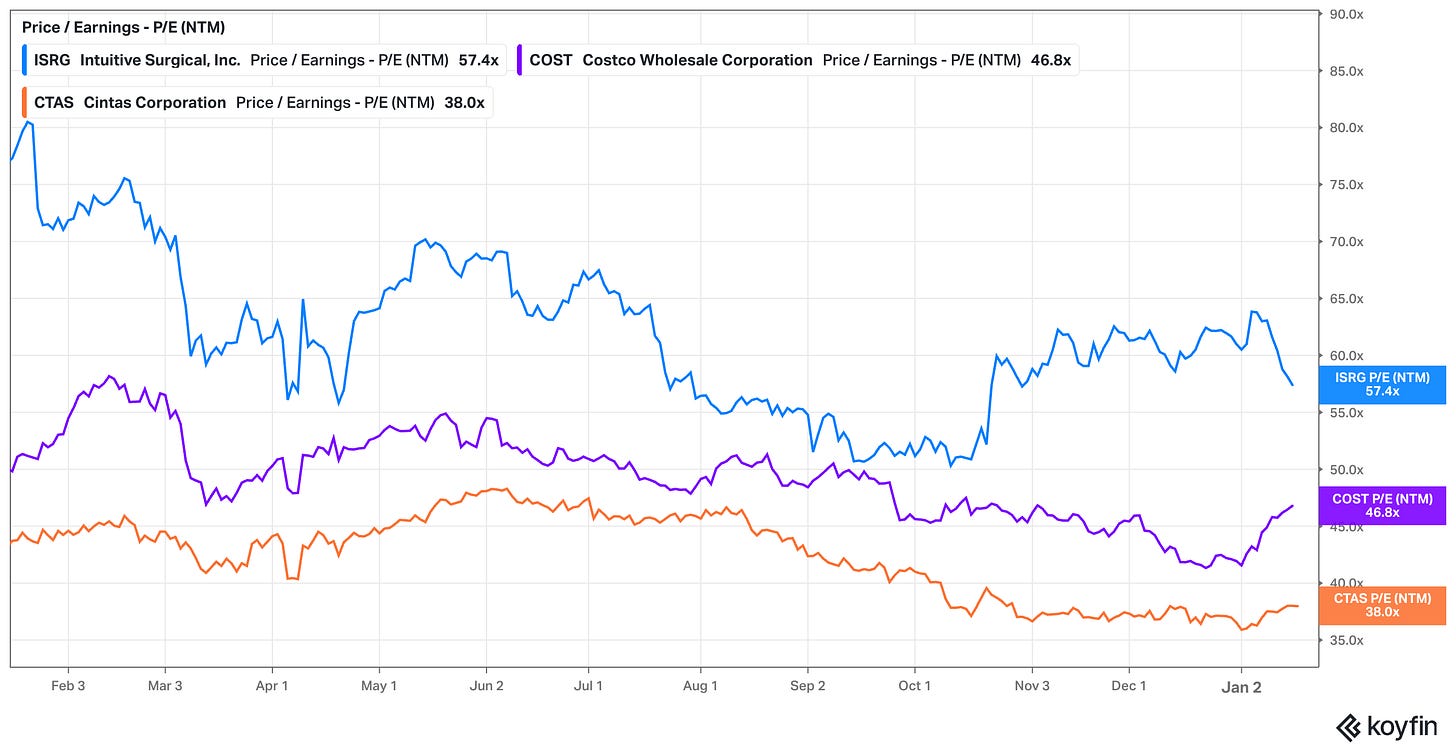

It’s hard to argue that companies like Intuitive Surgical, Costco, and Cintas aren’t great businesses, but at their current price/earnings multiples, anyone who still claims to be a card-holding member of the Value Club has to be skeptical of future returns.

I’m not going to make a case that these three stocks are cheap (or expensive) today, nor am I suggesting that you want to buy high multiple stocks as a group.

What I am going to introduce are ways that investors can better capture the potential for exceptional fundamental performance when determining fair values.

It might just save us from making return-impairing decisions.

Consider the recent example shared by Henry Ellenbogen on the Invest Like the Best podcast in which his former employer, T. Rowe Price, sold their early and prescient position in Walmart.

And obviously Walmart became Walmart. And I went back and I looked and I was like, wow, this is definitely one of the 20 stocks that mattered. But actually, unfortunately it was sold. And the math at the time was the retail fund—I think I was managing about $8 billion, which was the largest pool of small cap growth money in the country. And had the stake in Walmart not been sold, the stake in Walmart would’ve been greater than the sum total of everything that I was managing.

And I’m not saying people had made bad decisions before, but actually the math was one bad decision, or maybe you had to make that decision every day because the public markets are open every day, actually wiped out all these other good decisions, mathematically, they had done.

Hindsight is 20/20, of course, but research has shown that only a handful of Super Stocks account for the majority of stock market returns. If you don’t give yourself a chance to own one of them, it becomes more difficult to outperform the market, which will own them as a matter of course.

Value investors are a skeptical bunch, whether by nature, by study, or through our own experiences. We’ve seen enough once glamorized companies sputter out to conclude that it’s better to avoid those situations, so we’re eager to take our gains when it seems everyone agrees it’s a great company.

In other words, we manage for the rule rather than the exception.

But the exceptions are where the big fish are. If we want a chance at the exception, we must keep our minds open to the possibility that we may have one of them in our portfolio.

How can we do this while still maintaining our value investing discipline?

Let’s consider some ways to do it.