How Consumer Surplus Impacts Pricing Power

Building pricing power in competitive markets depends on the spread between price and value

Knowing what price to charge for your product is a major challenge for business owners. Charge too much and no one buys anything, charge too little and you’ll generate sales but won’t turn a profit. Neither practice is sustainable.

To determine pricing and your pricing power, it helps to put yourself in the customer’s shoes.

Whether we realize it or not, our consumer brains are constantly running price and value calculations. We won’t buy an item if the price is above our perceived value, but we’re happy to spend when perceived value exceeds the price. In other words, we’re seeking consumer surplus.

Let’s illustrate with an example.

If it’s a cold day, your brain might tell you that an average quality lemonade at a farmer’s market is worth $1 per cup, in which case a lemonade selling for $2 a cup is unappealing. If the vendor is charging $0.50 per cup, however, you might find value in it despite a lack of need.

On a hot summer day, that same lemonade at the farmer’s market might be worth $10 a cup to you. You’ll make a bee-line for a vendor selling the same lemonade for $5. However, if an overzealous vendor is charging $15 a cup, you’ll seek an alternative refreshment even if you really want a lemonade.

Pricing is driven by relevance. Pricing power is driven by consumer surplus, or the spread between price and value.

Cold lemonade on a hot day is relevant. Customers have an immediate problem (being sweaty and uncomfortable) and a frosty lemonade directly solves that problem, however temporarily. A cold lemonade on a cold day, in contrast, is less relevant as there isn’t a pressing problem.

As such, the price of a cold lemonade on a hot day should be higher than the price of a cold lemonade on a cold day. A rising price can therefore reflect rising product relevance - a good thing assuming costs don’t rise at the same rate - but whether or not a company selling the product has pricing power is a different question.

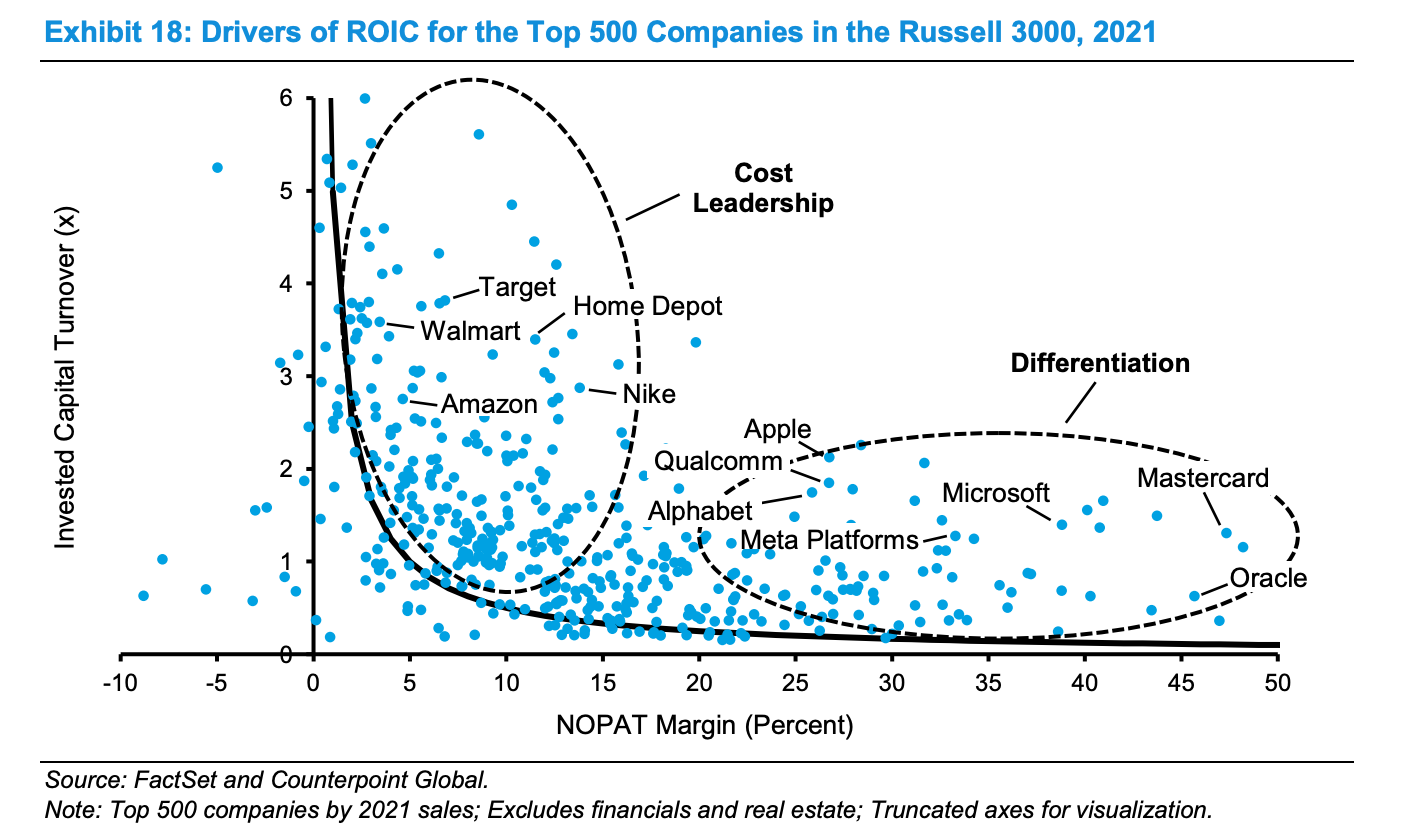

Pricing power is achieved in one of two ways - cost advantage and differentiation. The goal of both is to establish a spread between price and value.

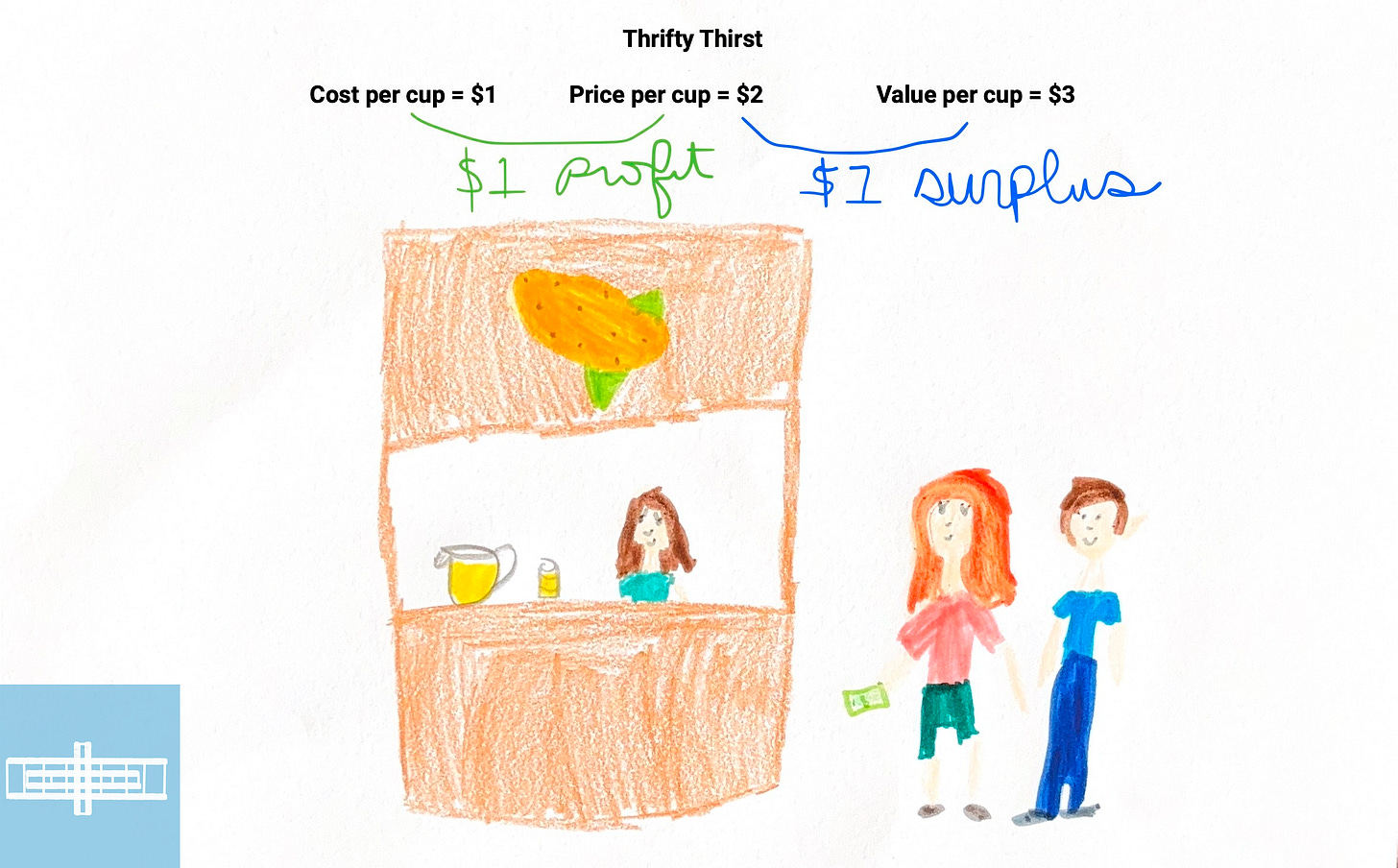

Let’s stick with the lemonade stand to explain the two strategies with some helpful illustrations from my daughter.

Cost advantage

In this case, the lemonade stand - we’ll call it Thrifty Thirst - operates in a competitive market where the market price is $2.50 per cup. Let’s say customers assign $3 per cup of value.

If the cost is $1.50 per cup for all vendors, there’s $0.50 of consumer surplus (the spread between price and value) and $1 of profit (the spread between cost and price). Sales are brisk for all market participants.

If Thrifty Thirst finds a way to produce at $1 per cup using the same ingredients as its competitors, it can charge $2 per cup and make the same $1 profit as everyone else, but now it creates a full $1 of consumer surplus. Consumers will naturally make their way to Thrifty Thirst over the others because they are receiving more value for their money. As a result, Thrifty Thirst takes market share.

In response, if competitors are unable to replicate Thrifty Thirst’s lower cost structure, they must lower their prices to $2 - and accept lower profits - to achieve a $1 per cup consumer surplus and remain competitive. By accepting lower profits to stay price competitive, Thrifty Thirst’s competitors impair their ability to reinvest as aggressively at Thrifty Thirst, giving Thrifty Thirst an opportunity to widen its advantage versus its peers.

We tend to think of pricing power as the ability to charge higher prices, but pricing power is the ability to charge any price - higher or lower - that maximizes the customer’s value proposition while maintaining profitability.

In the above example, a lemonade vendor that tries to match Thrifty Thirst’s cost of production by using inferior ingredients doesn’t produce the same consumer surplus because its perceived value is also lower.

Cost advantage is at the core of Costco’s pricing power. The company flexed this advantage during 2022 when rapid inflation forced many of Costco’s retail competitors to raise prices to protect their margins. Costco, however, held price on its famous $1.50 hot dogs, its $4.99 rotisserie chickens, and decided not to raise its membership fees.

Here’s what former CFO Richard Galanti had to say in the May 2022 earnings call about Costco’s decision to maintain its membership fee price:

Given the current macro environment, the historically high inflation and the burden it's having on our members and all consumers in general, we think increasing our membership fee today ahead of our typical timing is not the right time.

No one would have blamed Costco for raising its membership fee in that environment, but Costco had the cost advantage that enabled strategic restraint. Consequently, a Costco membership became even more valuable to its members.

When Costco eventually chose to raise its membership fees in 2024, it did so more easily because its strategic restraint in 2022 built up goodwill and created more value for its members. The latest earnings report showed that Costco U.S. and Canada membership renewals stood at 92.7%, just a hair shy of the record of 92.8% set prior to the membership fee increase.

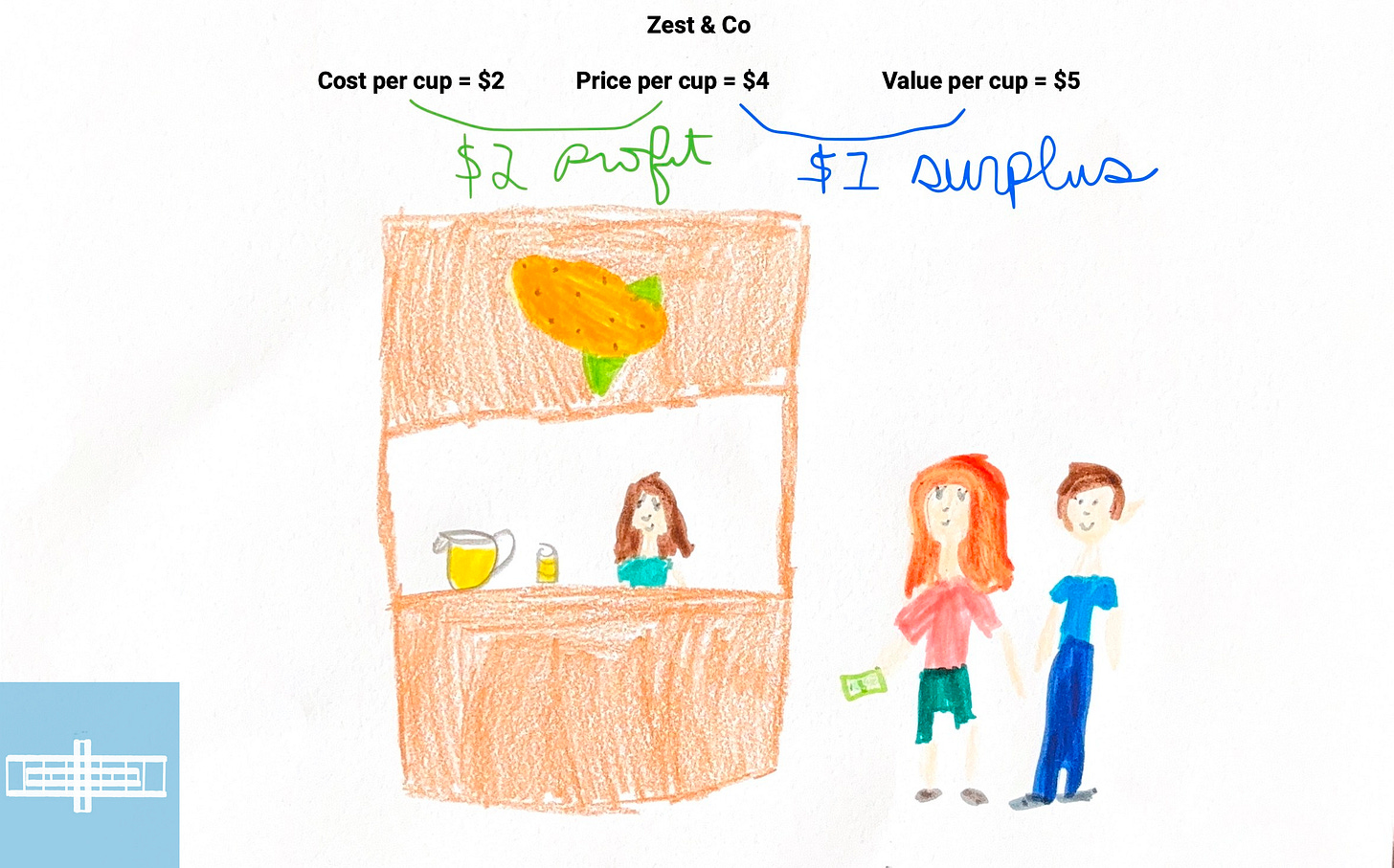

Differentiation

The second pricing power strategy is differentiation. Here, the company wants to increase the perceived value of its product in order to command a higher price and higher profits.

An enterprising lemonade vendor in a competitive market - we’ll call it Zest & Co. - may differentiate itself by promoting its use of quality ingredients.

Something like:

“Artisanal lemonade made from only the finest Brazilian sugarcane, Italian lemons, and Icelandic glacial water.”

Certain customers are likely to appreciate the added quality and boost their perceived value of the product.

In the previous case, we said the cost to produce an average quality lemonade was $1.50 for a cup, the market price was $2.50, and the perceived value was $3. Profit per cup is therefore $1 and consumer surplus is $0.50.

Here, Zest & Co. sees an opportunity to differentiate with premium ingredients to boost perceived value to $5 per cup. If successful, even if Zest & Co. charges $4 per cup and it costs $2 per cup to produce with higher quality ingredients, profit per cup doubles to $2 and consumer surplus jumps to $1 per cup.

The higher price point plus the consumer surplus can help Zest & Co. establish a premium brand. Consumers walking by with cups emblazoned with the Zest & Co. logo signal to passersby that “this person has discerning taste and the discretionary income to afford a premium priced beverage.” This can extend Zest & Co.’s higher perceived value to a broader audience and contribute to its ability to raise prices to offset cost inflation.

This is what Starbucks did to the U.S. coffee market in the early 1990s. Prior to Starbucks, most “to-go” coffee in America was obtained at a gas station and freeze-dried coffee was standard fare in American homes. Here’s how Starbucks founder Howard Schultz described the idea in his book Pour Your Heart Into It:

“What we proposed to do at Il Giornale [Starbucks predecessor], I told them, was to reinvent a commodity. We would take something old and tired and common - coffee - and weave a sense of romance and community around it. We would rediscover the mystique and charm that had swirled around coffee through the centuries. We would enchant customers with an atmosphere of sophistication and style and knowledge.”

Differentiation-based pricing power relies on consistent marketing and product quality to maintain a premium image. To be successful means you have to continue to be, well, different.

Squandering surplus

Pricing power becomes a liability when the spread between price and value is eliminated.

In the cost advantage example, Thrifty Thirst would squander its pricing power if it skimped on quality to maintain its cost advantage. Going cheap on ingredients might work for a few quarters, but eventually customers catch onto the lower quality and reduce their value perception.

In the differentiation example, Zest & Co. would squander its pricing power if it raised prices to the point where it matched perceived value. While this might juice (pun intended) short-term revenue or support margins, it would eventually lead to lower traffic due to alienated customers. Since price now equals value, customers no longer receive consumer surplus and will seek alternatives.

Evaluating pricing power

As you evaluate pricing power at your company or in a company you’re researching, start by considering which of the two strategies is being pursued.

Both approaches can work and lead to an economic moat that supports high returns on invested capital.

Once you’ve identified the approach, pay attention to how management is executing on the strategy.

If we’re talking about cost advantage, how does management drive costs lower, which enables it maintain a spread between price and value while earning a suitable margin? Is there a low-cost culture that permeates the company and reinforces the cost advantage?

For differentiation, how does management’s strategy keep pushing the perceived value higher, which enables it to raise prices without the fear of losing customers? Is the company innovating and reinvesting enough to maintain its differentiation?

Ultimately, we want to better understand the durability of a company’s pricing power. A temporary boost in consumer surplus gained through a cost advantage or differentiation is one thing, but if competitors can easily replicate the strategy or if management is on the path to squandering its advantage, the consumer surplus quickly disappears and is inconsequential to value creation.

For both business owners and investors, understanding the spread between a product’s price and value is key to gauging a company’s long-term value creation potential.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

Todd Wenning is the founder of KNA Capital Management, LLC, an Ohio-registered investment advisor that manages a concentrated equity strategy and provides other investment-related services.

At the time of publication, Todd, his immediate family, and/or KNA Capital Management, LLC or its clients did not own shares of any company mentioned.

Please see important disclaimers.