Letting Go: Why Selling is so Hard to Do

For long-term investors in quality businesses, deciding to sell down or fully exit an investment can be an agonizing process. Behavioral biases and personalities can complicate these decisions.

Audio version:

“Success does not lie in sticking to things. It lies in picking the right things to stick to and quitting the rest.” -Annie Duke

Ask most long-term investors under which conditions they would sell a stock, and the response is usually a combination of the following three reasons:

The stock has reached our fair value estimate,

There’s a better opportunity elsewhere, or

The thesis has changed.

These are all fair, logical reasons to sell. However, there are significant challenges with each, and they don’t make the selling process any easier. In today’s post, we’ll explore these challenges and consider ways to improve our approach.

Fair value

Classic value investing says: “Buy 50 cent dollars and sell when someone offers you the dollar.”

Naturally, then, we think we should sell when a stock reaches a “dollar” - our fair value estimate. But we’re not dealing with literal dollars, of course, we’re dealing with value-creating (or destroying) assets.

Now, if you’re investing in value-destroying assets, you should absolutely take that dollar before it becomes 90 cents. The answer is not so clear with value-creating assets.

Starting with a philosophical angle, what does “fair value” mean? The “fair” part implies there’s price at which the investment could change hands, with each party satisfied with the outcome.

Indeed, a fair value estimate derived from a DCF model says that at fair value, assuming no changes to the forecast, the stock price will grow at the cost of equity minus dividend yield from that point forward.

For example, let’s say you derive a $100 fair value on a stock using an 8% cost of equity, and the stock doesn’t pay a dividend. Assuming the forecast is unchanged, the fair value is $108 one year later.

Another way to think about it is buying a 50-cent dollar that becomes $1.08 in a year, $1.17 in two years, etc.

You may sell to an investor who is perfectly happy with that 8% return. To them, that’s a fair trade. And unless you have another investment with the potential for more than 8% returns, you should think twice about selling.

The second issue with “sell at fair value” is knowing when to say when on updating inputs. Yes, modifying a fair value estimate as new information comes in is reasonable, and you should absolutely update the fair value if a company performs differently from your expectations.

A rising stock price, however, can mislead you into upgrading your fundamental outlook. You start to wonder, “What might I be missing? Surely, other investors are seeing something that I’m not.” You worry that you’re selling just as the stock is about to really take off.

It’s a good line of inquiry; however, if you can’t find a reason to update your forecast, it’s a sign to sell.

Finally, selling a stock rapidly approaching your fair value estimate is not easy. Naturally, you want to maximize your return on the financial investment, but subconsciously you also want to maximize the return on your intellectual and personal investment. You may have made a bold contrarian bet and lost sleep when you first invested. You may have spent years researching the company and genuinely enjoy following it. Cashing in may not feel good.

How can we overcome mental and behavioral obstacles to selling a stock that reaches fair value?

Resist the temptation to tinker with the terminal assumptions in your model. Most of a company’s value in a DCF comes from your terminal assumptions about growth, risk, and profitability. Updating your 1–2 year outlook won’t materially impact your fair value, but seemingly minor changes to the terminal outlook can. Once established, terminal inputs should have a “break in case of emergency” sign over them. It is best to leave them alone unless you have a real and material reason to change your terminal inputs.

When investing in a cyclical business, there’s an idealized scenario where you buy at the bottom and sell at the top of the cycle. If it was easy, everyone would do it. Instead, it’s a job well done if you can exit or sell down a position in the top quarter of the cycle.

Remember that you don’t have to completely sell out of a position once it hits fair value. If you owned an exceptional private business, would you cash out at a “fair” price? No, you’d wait for some premium before accepting a full buyout. The public market allows us to sell down a position in pieces. You can own a wonderful business indefinitely if you’d like to, but you don’t have to make it a top position in all scenarios.

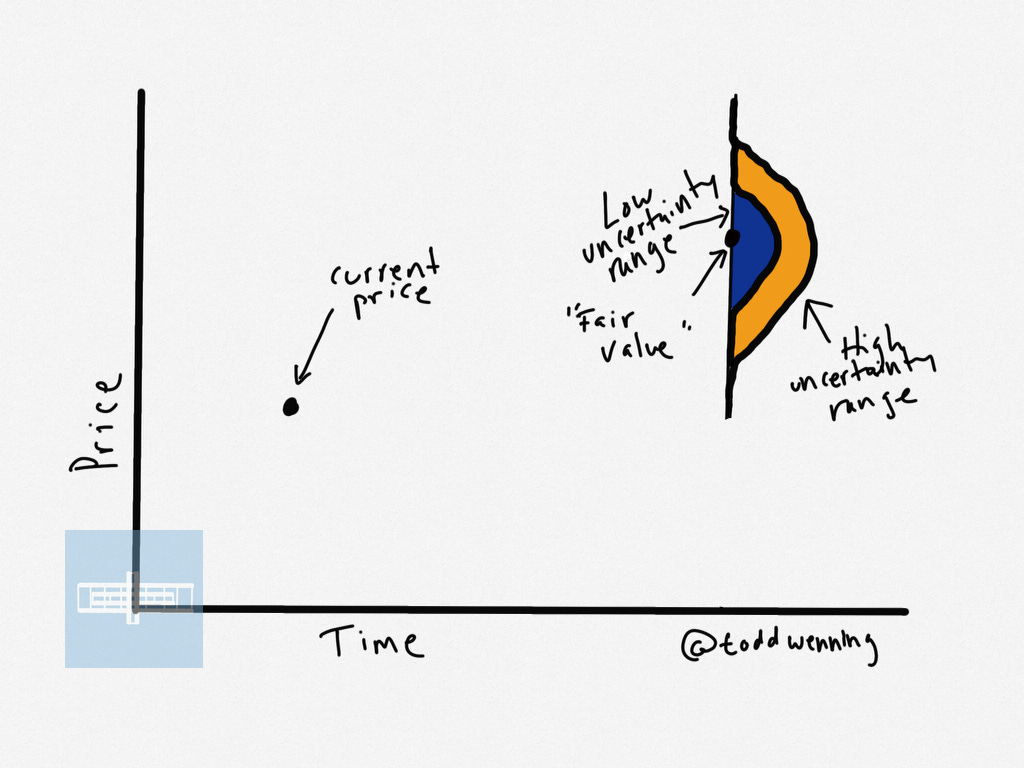

Think in ranges. It’s tempting to anchor into a down-to-the-penny fair value estimate, but that figure should represent your estimated most likely outcome. As illustrated below, one approach is to imagine distribution curves around your base case fair value estimates representing future free cash flow certainty. The more uncertain you are about a company’s future cash flows, the wider the range of potential outcomes and values.

Better opportunities elsewhere

While there’s tremendous value in learning about a small set of companies over many years, the lifeblood of an analyst is in finding new ideas. Even if it’s to stretch the imagination and learn about new competitors, business models, etc., a passionate investor should always be turning over rocks.

However, when a new idea gets interesting, you wonder if it should replace an existing position. But which one?

The longer you hold onto a successful position, the more likely you will place a halo on it and not want to sell. Conversely, you will likely resist taking the loss with an underperforming position, hoping it will at least get back to break even. These biases are obstacles to swapping out an existing idea for a new and better one.

To remove some emotion from the equation, quantify your qualitative judgments about each company. Rank characteristics like moat, management, and financial strength relative to your other holdings. If a new idea has better rankings than one treading water at the bottom, the bottom rank is the one to go.

Another approach is the “blank sheet” test. If you were starting the portfolio from scratch today, would you rather own the current holding or the new idea?

Thesis changed

Companies aren’t static assets. Over the next decade, the company you buy today will change and get better or worse. As Buffett said in the 1987 shareholder letter:

“After ten years on the job, a CEO whose company annually retains earnings equal to 10% of net worth will have been responsible for the deployment of more than 60% of all the capital at work in the business.”

A lot can change in a decade, even at stable companies. Acquisitions, divestments, new CEOs, etc., are all common occurrences at blue-chip companies.

As such, every investment will have some type of thesis adjustment over the course of the holding period. However, thesis drift becomes a negative when something material has changed for the worse, and the investor explains it away.

You like to think that you’ll identify a material change in the moment, but it’s so easy to rationalize it away without an anchor to hold you accountable.

A remedy to this bias is to write down reasons to sell before the event occurs. What are some yellow flags that should require you to revisit the thesis? What are the red flags that should be an automatic sell?

Yellow flags might be changes in management or a change in the way a company reports segment results. As in soccer, two yellows may equal a red. Red flags could be awareness of management discord or a moat-diluting acquisition.

A final strategy is to take a page from Philip Fisher and consider something like his “three-year rule” for selling. That is, you sell the position if the company doesn’t do what you expect it to in three years.

It can seem like an arbitrary line in the sand, and you naturally worry that the company will turn itself around right after you sell. However, at some point it becomes clear that inertia is going to win out and you need to fold up your tent.

What are you afraid of?

What is it that keeps us from selling a stock? Whether it’s gone up or down, many times, what we’re worried about is regret. We’ll feel stupid if the stock goes up afterward. Even worse, the stock we bought instead might go down while the one we sold goes up.

Investing is a decision-making business and regret is always just around the corner. If we’ve done good work and feel strongly about selling (or buying), we must come to terms that something could go wrong and be comfortable with that. Otherwise, we’ll be unable to make decisions. As Daniel Kahneman said in an interview with Morgan Housel, “You need to inoculate yourself against regret.”

As painful as regret can be when things go wrong, it’s also a great teacher. If you regret buying a particular car brand, you won’t buy another. Likewise, if you regret selling a great business too soon, you’ll think twice when the scenario reappears (and it will). As Randy Pausch said, “Experience is what you get when you didn’t get what you wanted.”

Why sell at all?

To be sure, investors intent on only owning great businesses should be hesitant to part with their shares. “Do nothing” is a reasonable default when you have a wonderful business that’s undervalued.

As Philip Fisher wrote in Common Stocks and Uncommon Profits, you have a much higher success rate determining whether or not you’ve found a quality business than you do figuring out how the stock will perform in the next few months. As such, Fisher argued, “both the odds and the risk/reward considerations favor holding.”

Buffett echoed this sentiment in the 1987 Berkshire shareholder letter, saying:

“We look at the economic prospects of the business, the people in charge of running it, and the price we must pay. We do not have in mind any time or price for sale. Indeed, we are willing to hold a stock indefinitely so long as we expect the business to increase in intrinsic value at a satisfactory rate.”

He followed up a year later on this topic, adding:

“When we own portions of outstanding businesses with outstanding managements, our favorite holding period is forever. We are just the opposite of those who hurry to sell and book profits when companies perform well but who tenaciously hang on to businesses that disappoint.”

The common denominator between Fisher and Buffett’s comments is that holding is preferential as long as the business remains wonderful.

It’s important for quality investors to be on guard against quality traps. As this chart from a recent paper by Michael Mauboussin and Dan Callahan shows, the worst-performing cohorts of ROIC quintiles were the two who started in the highest quintiles and ended up in the lowest quintiles three years later.

Said differently, the market punishes quality companies that fail to meet expectations. Consequently, quality-focused investors need to pay the most attention to moat trends - is the moat getting wider or narrower? - and be prepared to sell when the moat begins to narrow.

Additionally, there are times when the market offers considerable premiums for high-quality businesses. Not taking some off the table in those situations and failing to reallocate to other opportunities can also prove a mistake.

Selling is hard

Selling is a portfolio management tool and a means for managing risk.

Similar to the discussion we had about position sizing, much depends on the individual’s personality. Some investors prefer not to sell at all; others are more active. Either way, you’re making selling decisions (deciding not to sell is still a decision), and we’re in a decision-making business. There’s no one correct answer, but awareness of the biases and challenges inherent in selling decisions – particularly how sensitive we are to regret - is the first step in improving our decision-making processes.

How do you approach selling in your portfolio? Let me know in the comments below.

Stay patient, stay focused.

Todd

Disclaimer:

This material is published by W8 Group, LLC and is for informational, entertainment, and educational purposes only and is not financial advice or a solicitation to deal in any of the securities mentioned. All investments carry risks, including the risk of losing all your investment. Investors should carefully consider the risks involved before making any investment decision. Be sure to do your own due diligence before making an investment of any kind.

At time of publication, the author or his family may have an interest in the securities mentioned or discussed. Any ownership of this kind will be disclosed at the time of publication, but may not be updated if ownership of a particular security changes after publication.

Information presented may be sourced from third parties and public filings. Any links to these sources are included for convenience only and are not endorsements, sponsorships, or recommendations of any opinions expressed or services offered by those third parties.

I use rule #2, which I call the economic sell rule. In trading individual bonds, a good bond manager has a handful of rules to figure out whether swapping one bond for another is a good idea or not. Things are more vague for a manager of stocks, but most managers should have a rough sense of how promising each stock is... which could be expressed by position size. Thus virtually all of my portfolio trades are swaps of one position for another, which forces me to be businesslike in my limited trading.

I heard Howard Marks say in an interview once that selling is un-buying. I've found thinking about selling in that framework useful. Taking a position back through your buying process and thinking about the reasons to continue to own it VS the reasons not to can be helpful.